Objection Against China’s Zero-COVID Policy Raises Dangers and Hopes for Chinese Individuals

January 15, 2023

China’s zero-COVID policies have both been praised and heavily criticized on an international scale. These policies include severe lockdowns of entire neighborhoods for a singular case, and notably, forcing people into quarantine camps where they are kept in the thousands with little to no amenities. Not only has it been costly to the economy—causing over 70 million people to lose their jobs—but it has also been condemned for violating the rights of Chinese citizens. Nearly three years after the initial lockdown in Wuhan, Chinese citizens have begun to protest these extreme policies. Campuses around China and in US cities, including Cambridge, have all demanded that Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Leader Xi Jinping resign. Though initiating against strict COVID policies, the protests have extended into objecting government censorship and authoritarian rule—sending both hope and terror through Chinese people all over the world.

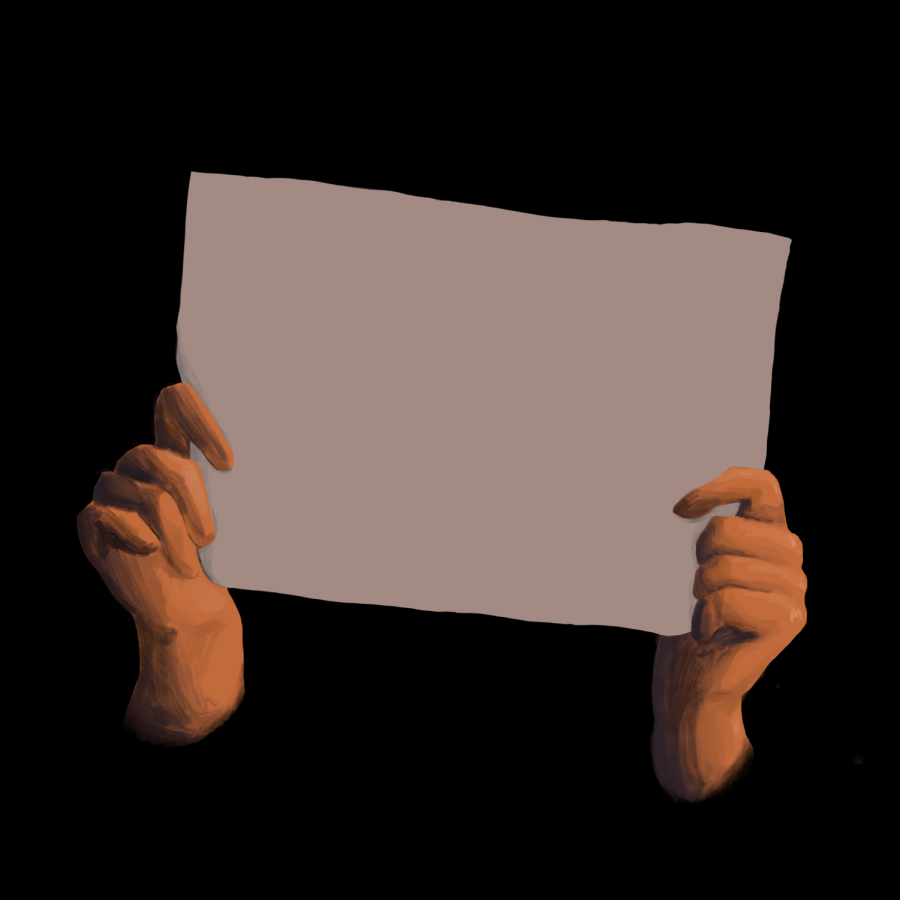

Had you walked into any of the major Chinese universities in late November, you would see multiple people holding up a blank sheet of paper, a symbol demanding the overthrow of the CCP. The blank sheet was used to avoid imprisonment from China’s harsh censorship laws while demonstrating everything but fear. According to a protester on Reuters, “The white paper represents everything we want to say but cannot say.” Without any writing, the government has no grounds for arrest, while the empty paper still sends a strong message of rebellion.

Although getting the message across, these demonstrations spark fear in not only Chinese citizens, but also Chinese people abroad. Amy Zhou ’24, upon hearing of the protests, stated to the Register Forum, “My initial reaction was fear—just because of how the Chinese government tends to respond to opposition.” Historically, the CCP has punished protests with imprisonment, threatening family members, and even death. Zhou adds, “It’s good that people are voicing their opinions when it concerns their freedom, but I’m concerned about government backlash because China doesn’t have the best track record when it comes to free speech.” While in the U.S., protests are acknowledged as a civil right, in China, repercussions are acutely felt.

The policies question the morality of governmental actions and how this may have been used as a political play. Chloe Wang ’23 stated, “The lockdowns and censoring are a bit excessive,” citing the censorship of the ongoing World Cup due to the unmasked audience. Critics of Xi have said that these policies are a tool to push a utilitarian agenda instead of a moral one. Alina Patwari ’24 told the Register Forum, “The policies make sense scientifically, but science hasn’t always been ethical.” Patwari continues by saying, “[The CCP] needs to understand that they’re dealing with a population of people and not simply a disease.”

These protests have ultimately stemmed from more than COVID policy. The gatherings have questioned the extent a government has to limit one’s freedom. And while the West has been quick to criticize, many have pointed out that this is a more aggressive version of mask and vaccine mandates. However, from a policy standpoint, the gradient into the extreme is becoming vaguer and vaguer. In China, that standard seems to be clear, seeing as objections to the entire form of the Chinese government are rising. Whether that will be effective is unknown, but as of Wednesday, December 7, 2022, the CCP announced that certain aspects of zero-COVID have been eased. Though this is far from meeting demands, it shows an unexpectedly high degree of progress. What lies in store for one of the world’s most powerful governments is still unsure, but the power of protest—whether dangerous or productive—is being exemplified in China.