Forgotten, but Not Finished: The Stop Asian Hate Movement

June 7, 2022

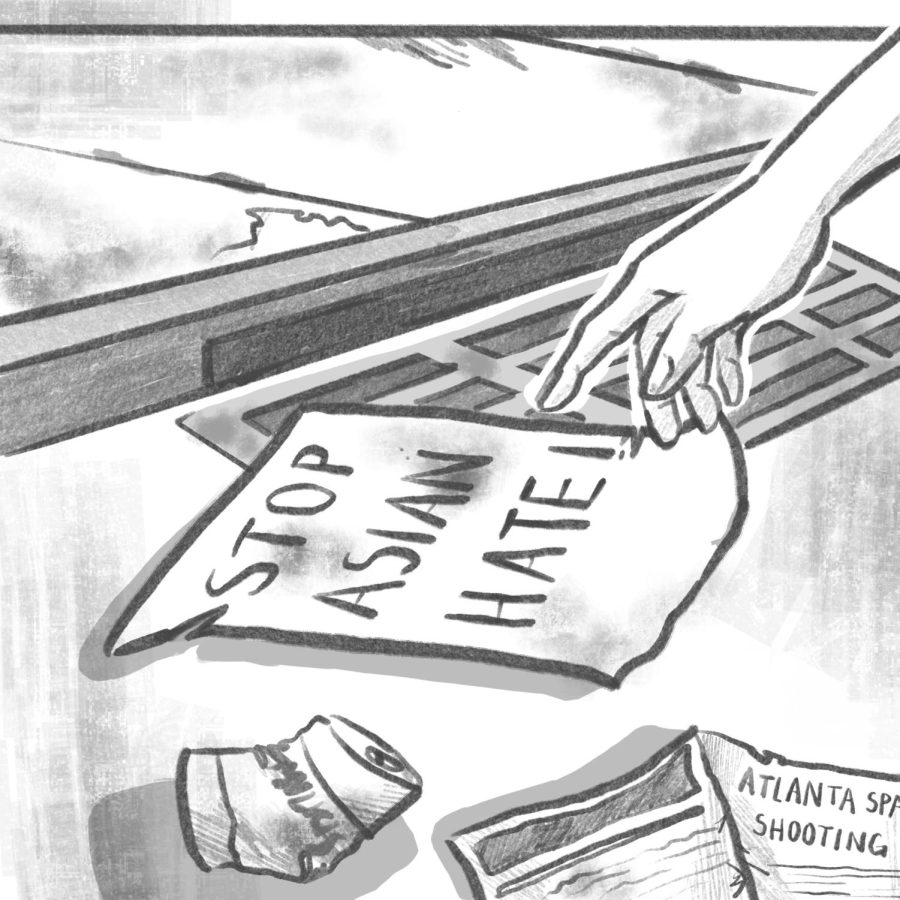

Following the Atlanta spa shooting in March 2021 and the Indianapolis FedEx shooting in the following month, media coverage of Asian American & Pacific Islander (AAPI) hate hit an all-time high, with all major media platforms covering these events. A week after both shootings, coverage died down to the point where it would seem like AAPI hate suddenly ended. Although media coverage of AAPI hate has become scarce, the high percentages of hate crimes have stayed steady during the past few months.

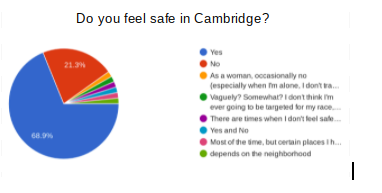

In a Google survey sent out to CRLS students, 93.8% of survey takers said they had not seen any news on AAPI. When asked about decreasing media coverage, CRLS Student Body Co-President Jinho Lee ’22 replied to the Register Forum that, “[it is] because of a rise in performative activism, or outcry activism. When a movement comes to prominence, many people let it be known that they care by informing others about it. However, after a tiny bit of time passes, their interest dies down as soon as they feel like they’ve done enough. This is problematic because hate crimes don’t have an end to them.” In addition to the Stop AAPI Hate movement, many other movements in the US, such as the Black Lives Matter protests which were incited by the murder of George Floyd, fall victim to being abandoned by the media.

According to the organization Stop AAPI Hate, 55.7% of the AAPI hate crimes that occurred in the past two years took place in 2021. The New York Police Department recorded a 361% increase in AAPI hate in 2021, adding to the almost 800% increase in 2020. When students were asked about why this hate persists, Laila Clarke ’22 told the Register Forum that, “East Asians are often told that they don’t face as much racism as other people of color, and not everyone has been taking this as seriously.”

During the civil rights movement in the 1960s, as Black Americans fought to abolish institutional racism and discrimination, Asian Americans—being seen as less of a threat—were used by White Americans as a model for how minorities should act. After many newspapers covered the “Model Minority” stereotype, Asian Americans created movements to fight for social issues inspired by the Civil Rights Movement. This idea of Asian Americans being a “Model Minority” erases the trauma, discrimination, and hate Asians have faced in the United States for hundreds of years.

Though Asia is a massive continent with hundreds of nations and thousands of ethnicities and cultures, the idea of a “Model Minority” removes the diversity of Asians and puts them all into one group. Many people who are not of Asian descent struggle to tell the difference between people of different regions of Asia: South Asians are commonly perceived as Indian, and Southeast Asian and East Asians are perceived as Chinese. The trope also divides BIPOC communities by making it seem as if one group is superior to another, which is untrue.

The anti-Asian sentiment is even present in elementary and middle schools. Matthew Liu ’22, the Co-Vice President of the Asian Club, said that he “was one of the few Asian students at my middle school. I was often excluded, and in many cases, racial slurs and gestures were directed towards me.” Making fun of Asians is mainstream and normalized in American society; by alienating Asians and their cultures, ignorance is empowered, and even in a progressive city like Cambridge, racism thrives.

Sumbul Siddiqui is a third-term City Council member and the current Mayor of the city of Cambridge who recently won a second term. Mayor Siddiqui is a native Cantabrigian, Pakistani American, and the first Muslim to be elected mayor in Massachusetts. During her sophomore year at CRLS, her history teacher had pulled up news about a terror attack. According to Siddiqui, “he saw my last name in front of the TV and asked me in front of the class if I was related to an alleged terrorist.” Although he apologized later, revealing that he did not intend to hurt her, the fact that he believed she was connected to a terrorist because of her last name was a painful and embarrassing memory. Even on the campaign trail, Mayor Siddiqui faced many calls and emails targeting her identity and whether she was “really” an American citizen.

As a woman of color, Mayor Siddiqui represents many underrepresented BIPOC communities as she is often the only person of color in the room. Because of this, much pressure is put on her. “When you’re the first something, you have to be presented positively or have negative consequences. I have to be conscious of everything I do and how I’m showing myself, and my office is not offensive.” Society tends to put people of color into groups rather than judging them individually. Unfortunately, if one individual does something terrible or makes a mistake, a larger group of people are judged together.

Steps must be taken at local and national levels to help combat AAPI hate. The United States must denounce past anti-Asian rhetoric and increase Asian visibility. Dialogue must take place so that BIPOC communities can have better relationships. Real and present racial issues should not be turned into social movements with expiration dates, and martyrs should not be made of the people who are victims to them. Even as CRLS students are given the opportunity to take the Asian History elective next year, Co-President Yonas Aschale ’22 reminds the Register Forum that the fight against AAPI hate is not over, and that, “This is an issue that cannot be stopped in a few months or even a few years. Children must be taught at a young age about different cultures and ethnicities present in the US to be able to humanize them. Hate is fueled by ignorance, and by ending that ignorance, then we can truly end these hate crimes.“