Aung San Suu Kyi and Her Journey from Democracy to Authoritarianism

February 26, 2021

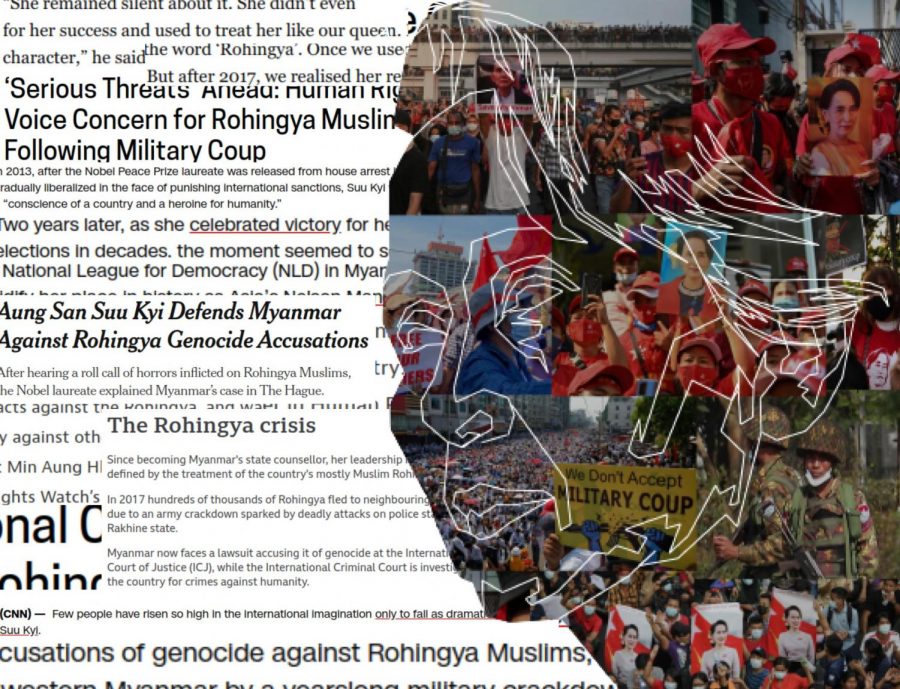

On Monday, February 1st, 2021, the Burmese army took over the reins of power in Myanmar, arresting President Win Myint and head of government Aung San Suu Kyi, a Nobel Peace Prize winner. This putsch comes a few months after the elections in Myanmar which strengthened the majority of Kyi’s party (The National League for Democracy) in parliament, winning 80% of the vote. It was during the first assembly of parliament that the military intervened, protesting claims of electoral fraud. Although recently criticized for her attitude towards the abuses of the Burmese army against the Rohingyas, Suu Kyi remains adored in her country and receives the support of the international community which has strongly condemned her detention.

For a long time, Suu Kyi was the icon of the democratic transition in Myanmar. Her ancestry gives her the air of a tragic heroine: “the Burmese Antigone” is the daughter of the figure of independence Aung Saun, assassinated when she was only two years old. In 1988, she left her British exile to return to Myanmar and take the reins of the fight against the dictatorship by co-founding the National League for Democracy. That year, a popular rebellion claimed some 3,000 victims. “I could not, as my father’s daughter, remain indifferent to everything that was happening,” she claimed during her first speech in power. The military junta placed her under house arrest in 1990.

It was there–on the shores of a Yangon lake, where she spent twenty years deprived of her liberty–that the international community hoisted her on the throne of planetary peace. In 1991, Aung San Suu Kyi received a Nobel Peace Prize, all the more symbolic that it would take her twenty years to be able to pick it up from Oslo.

After her release in 2010, Suu Kyi began to tarnish her pious image in the world of “realpolitik.” Some blame her for her authoritarian tendencies, others for a certain coldness. “I am a politician, I am not and will not be Margaret Thatcher, but I am neither Mother Teresa either,” she confided in 2012 to the press. Despite her strict politics, she managed to draw popular support in Myanmar due to her important economic reforms on the path to development. Aung San Suu Kyi won the 2015 legislative elections and the following year, she became the “Special State Advisor and Spokesperson for the Presidency,” which de facto corresponds to a position of head of state due to a sexist constitutional provision prohibiting her the presidency.

The myth surrounding Suu Kyi suddenly collapsed in 2017 with the massacres carried out by the Burmese army against the Rohingya minority. Over 700,000 people from this Muslim minority were forced to take refuge in Bangladesh to flee the abuses. When the UN Independent Commission of Inquiry criticized her for not having “used her moral authority to counter or prevent the killings,” Aung San Suu Kyi remained silent. Canada and several British cities withdrew her honorary citizenship title. Her democratic image finally crumbled in 2018, when following the arrest of two Reuters journalists who were investigating the Rohingya atrocities, Aung San Suu Kyi called them “traitors for breach of state secrecy.” Suu Kyi’s international reputation has suffered greatly as a result of Myanmar’s treatment of the Rohingya minority, considering them illegal immigrants and denying them citizenship. Over the decades, many have fled the country to escape persecution. Suu Kyi appeared before the International Court of Justice in 2019, where she denied allegations that the military had committed genocide.

Because the Burmese political system automatically reserves 25% of the seats in both chambers and the Ministries of Defense, Interior, and Borders to the army, military personnel have slowly been growing in power. Faced with this concentration of opposing powers, Aung Saun Su Kyi advocated for “patience” and “negotiation.” These soldiers, who became the institutional right wing of the former dissident, overthrew her on Monday, February 1st, after having contested the general elections on November 8th for several weeks. On that day, Aung San Suu Kyi’s party had won 396 of the 476 seats in parliament, confirming the Burmese’s historical attachment to what they respectfully call “Dow Suu.” In a letter posted on social networks, Aung San Suu Kyi urged the people not to “accept this military coup.”

The military is now back in charge and has declared a year-long state of emergency. Power has been handed over to Commander-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing. He has long wielded significant political influence, successfully maintaining the power of the Tatmadaw (Myanmar’s military) even as the country transitioned towards democracy.

The protests over the coup have been the largest since the Saffron Revolution in 2007, when thousands of the country’s monks rose up against the military regime. Protesters include teachers, lawyers, students, bank officers and government workers. Water cannons were fired at protesters, and the military has imposed restrictions in some areas, including curfews and limits to gatherings.

The UK, EU, and Australia are among those to have condemned the military takeover. UN Secretary-General António Guterres said it was a “serious blow to democratic reforms.” US President Joe Biden has reinstated sanctions on the nation. However, China blocked a UN Security Council statement condemning the coup. The country, which has previously opposed international intervention in Myanmar, urged all sides to “resolve differences.”

The situation in Myanmar is quite ugly, and things have taken quite a dramatic turn this year. This coup is a direct testament to the downfall of Suu Kyi, sacrificing the country’s democracy along with it.