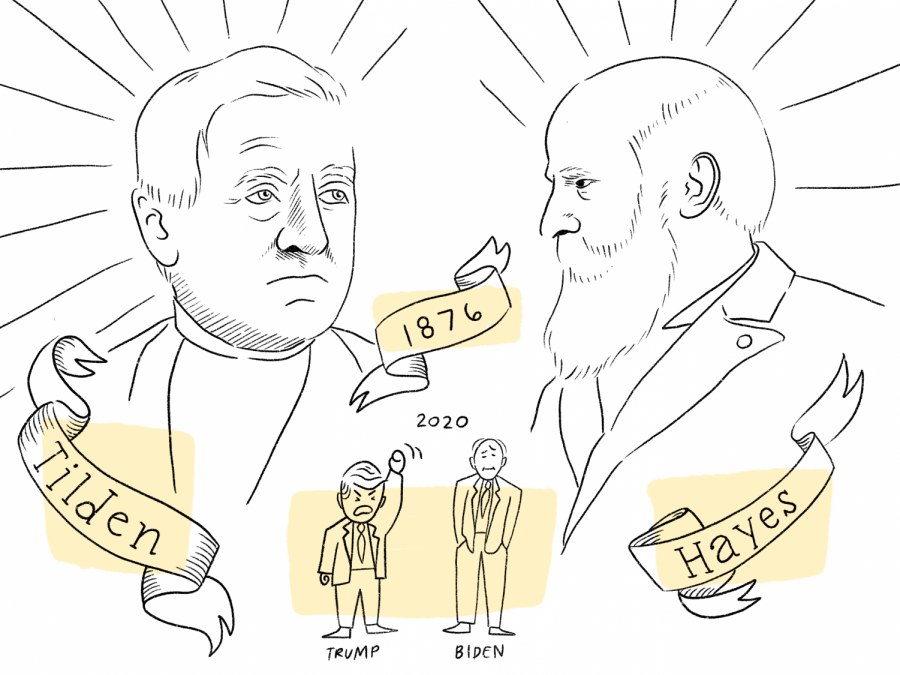

Hayes v. Tilden: the Most Divisive Election in United States History

January 28, 2021

On January 6th, before insurrectionists broke through Capitol security and interrupted Congress’ vote to certify Joe Biden as president, multiple Republican senators objected to the election results based on alleged voter fraud. Texas Senator Ted Cruz and Missouri Senator Josh Hawley were among them, referencing a precedent set in 1877 after the 1876 election results were unclear. This begs the question: How does that precedent come into play in 2021?

By the end of election day, 1876, the results in three states—Louisiana, South Carolina, and Florida—were unclear. Both the Democrat and Republican candidates for president claimed victory, and both Democrats and Republicans flocked to those three states to try to influence the outcome. Republican-dominated returning boards in these states had jurisdiction over which votes to count and which votes to discard if they were fraudulent. Returning boards in all three states discredited enough Democratic ballots to theoretically give Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes the majority in the electoral college.

At the same time, in Oregon, a Republican elector, John Watts, was revealed to be a postmaster. The Constitution does not allow “federal officeholders” to be electors, and so he was disqualified from voting. The Oregon governor was a Democrat and replaced Watts with an elector who favored Samuel J. Tilden, the Democratic presidential nominee. This caused Oregon to join the other three states as “uncertain,” as a third of Oregon’s electorate could go to either party.

The action shifted to the capitals of the three aforementioned Southern states. Two sets of electors from each of the states met. Democrats were outraged by the boards’ discarding of their party’s ballots, and thus they decided to have their own electoral vote. The competing sets of electors cast conflicting ballots, but both sets of ballots were signed by election officials.

Due to this, the two slates of votes for each state were sent to Congress to be certified.

At the time, Tilden was winning with 184 electoral votes, only a single vote away from victory; Hayes had 165 votes. But, there were 20 electoral votes still disputed, and Americans waited as Congress met and came to a conclusion.

Republicans in Congress argued that the President of the Senate, Republican Thomas F. Ferry, should have the power to choose which set of ballots to count. Democrats disagreed, arguing that a majority in the Democrat-led Congress should decide. Neither side agreed to the other side’s proposal, and thus, a compromise was born.

On January 29th, 1877, The Electoral Commission Act created a commission of five senators, five representatives, and five Supreme Court Justices. At the time, the commission was composed of seven Democrats, seven Republicans, and one independent Justice. However, Justice David Davis resigned after taking a senate seat and was replaced by a Republican Justice, Joseph Bradley. Democrats agreed to Bradley’s appointment even though it gave Republicans an 8–7 majority. But their agreement came at a price: The Republicans had to agree to remove federal troops from the South, thereby ending Reconstruction.

After this agreement, the commission cast its vote. In the case of the three disputed Southern states, the commission voted in favor of Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes. In the case of the Oregon elector, the commission reappointed John Watts in an 8–7 vote after resigning as postmaster. Watts cast his ballot and Hayes took the election 185-184. Just two days later, he became the 19th president of the United States.

So, how does this relate to the 2020 election?

No state’s results have been so heavily disputed to the point that two sets of electors voted. Furthermore, the election this time was not close like it was then. Tilden was one electoral vote away from the presidency. Trump was 36 votes away.

The precedent set in 1877 will likely never come into effect as voting machines have near-perfect accuracy. But, if two conflicting slates of electors vote again, then the Electoral Commission Act of 1877 will be a guide that Congress will follow. Until then, Hawley and Cruz’s proposition to reinstate the commission will continue to lack the support it needs to be passed through Congress.