True Detective: a Fresh Take on the TV Detective Genre

January 28, 2021

Popularized by shows such as Miami Vice, the TV detective genre has never been able to live up to its potential in the way Sherlock Holmes validated the medium of Conan Doyle’s age. Now run into the ground by shamelessly serialized franchises like Law and Order, audiences have grown numb to these vile presentations of rape and murder in between commercial breaks, pushing TV writers into a corner as they’ve exhausted ways to shock the viewing public. Police procedurals, as they’re often called, live up to that title of predictability: going through the motions of a crime, not once lending insight to the mind of the perpetrator. In television, you can give the audience every detail of who, what, when, and where, but it isn’t engaging until you’ve answered the why. It only makes sense then for the most worthwhile detective show in the last decade to emerge from a novelist, Nic Pizzolatto, seeking to enter into a new medium. Spanning three decades and thousands of miles, the investigation of True Detective is as much into its characters as the crimes they’re solving.

The investigation of True Detective is as much into its characters as the crimes they’re solving.

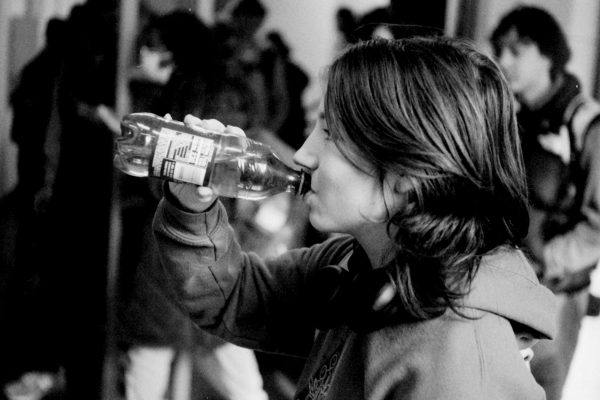

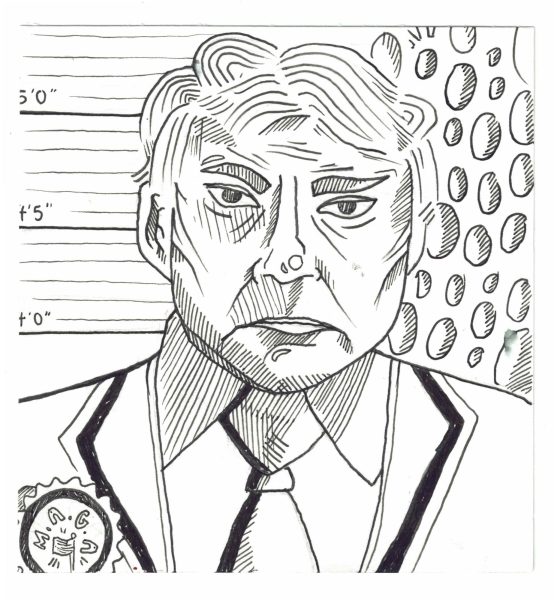

Framed in the opaque, boundless swamps of Louisiana, director Cary Joji Fukunaga expands the world of True Detective with dimension unlike that of even its most praised contemporaries. Even as the intricacies found in Pizzolatto’s conspiracy equal that of the best crime novels, the crux of the story still falls on its characters. In the series’ opener, we find the mouth of a rabbit hole in the thousand mile stare of Rustin “Tax Man” Cohle (Matthew McConaughey). Now twenty years distanced from his most haunting cold case, Rust more closely resembles a husk than a human being. After years of throwing his body and mind, Rust’s death wish is abated only by the presence of his given partner, Martin “Marty” Hart (Woody Harrelson). In a lesser drama, the conflict between ‘buddy cops’ is played up as a trope, tension to pad out the gaps of an otherwise original screenplay. Instead, we learn early on in True Detective how these two men differ ideologically, and then follow their butting of heads to its logical conclusion. While Rust might have nothing to lose in the pursuit of what he calls justice, Marty grounds him as a family man hung by guilt and insecurity. One conversation between the two halfway through the season sees Marty in a moment of weakness, unloading on Rust, “Do you wonder ever … If you’re a bad man?” And without meeting his partner’s eyes, Rust asserts: “No, I don’t wonder, Marty. World needs bad men.” In the dead silence following that line, the audience is immersed with these two characters for long enough to ask if Cohle believes his own words.

In their crusade for justice—or at the very least, answers—we witness the steep cost this investigation demands of our protagonists, continually finding something new to be lost, even in themselves. There must be a price paid for the truth, and it seems that for every length of rope climbed deeper into their shared descent, another layer of themselves is stripped away. The most explosive scenes in True Detective are shows of Cohle’s unwavering devotion to finding the truth with or without the law, a philosophy slowly adopted by Hart as he too wrestles to live without answers.

Whether it’s a crime scene or simply Hart and Rust trapped at home, every scene of True Detective feels like a new puzzle piece, with the cheat sheet just beyond your grasp. That same puzzle marinates in the minds of our protagonists for 20 years, following them home and seeming to bleed into every facet of their lives. The price for the truth is theirs to pay, but each is, in their own way, too selfish to pay it. Does avenging the death of a little girl forgive the sin of neglecting your own? These questions loom like rain over the eight episodes that compose the first season of True Detective, yet some carry after the credits roll, left intentionally for the audience’s interpretation. To leave it in Pizzolatto’s own words: “Nobody was gonna let me make a TV series that was just about two men, riding around, talking. So, I put a murder in there.”