Community Responds to Dr. Seuss Book Controversy

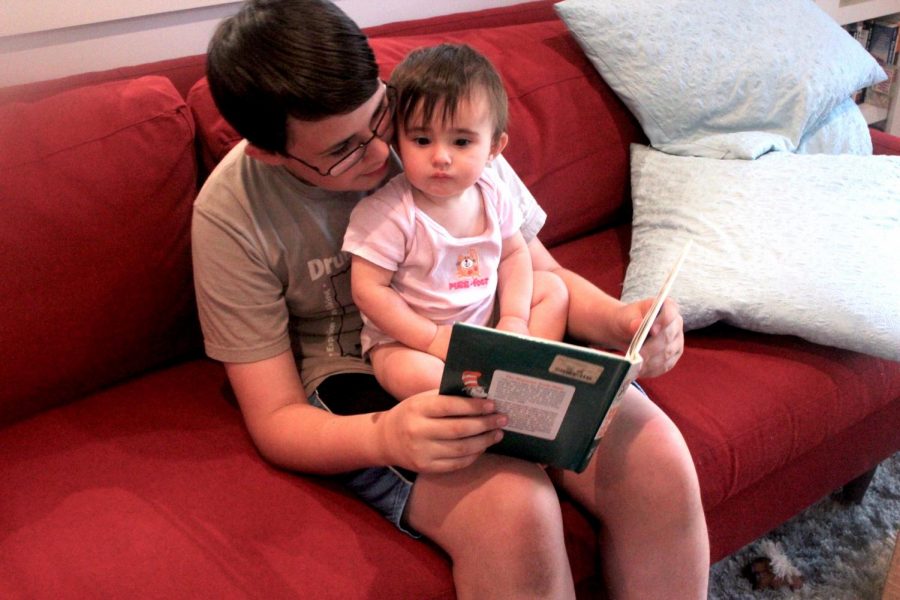

Dr. Seuss books are childhood favorites for many.

October 30, 2017

Cambridge made national headlines on September 28th when the librarian of the Cambridgeport School, Liz Phipps Soeiro, published a letter addressed to First Lady Melania Trump rejecting a donation from Ms. Trump of ten Dr. Seuss books.

Melania Trump sent books to the Cambridgeport School and other high-achieving schools across the country to celebrate National Read a Book Day on September 6th. In a letter accompanying the books, the First Lady advised children to take advantage of their education and let reading take them to places they never could have imagined.

In her letter to Melania Trump, Ms. Phipps Soeiro argued that instead of going to Cambridgeport, the First Lady’s gift should have gone to an underfunded school with more limited access to books, not a school like Cambridgeport where her students “have access to a school library with over nine thousand volumes and a librarian with a graduate degree in library science.”

Ms. Phipps Soeiro also argued that Dr. Suess is “a bit of a cliché, a tired and worn ambassador for children’s literature,” and that his books “are steeped in racist propaganda, caricatures, and harmful stereotypes.” In her letter, Ms. Phipps Soeiro cites a School Library Journal article that reports on Katie Ishizuka’s observations that one of Dr. Seuss’ most famous books, The Cat in the Hat, has similarities to blackface.

Kevin Dua, a psychology teacher at CRLS, thinks he can understand Ms. Phipps Soeiro’s reasoning behind rejecting the books. He noted that Cambridge has a “reputation of having a lot of resources,” adding, “I think for [Ms. Phipps Soeiro], she felt that these books could be of value elsewhere. I think as educators, I think we always try to think how we can help students, whether students who are in our classrooms, in our school building, or elsewhere.”

In response to Ms. Phipps Soeiro’s letter, East Wing Communications Director Stephanie Grisham said in a statement on behalf of Melania Trump, “To turn the gesture of sending young students some books into something divisive is unfortunate, but the First Lady remains committed to her efforts on behalf of children everywhere.”

The Cambridge Public School District released a statement in response to Ms. Phipps Soeiro’s letter, saying, “Cambridge Public Schools supports the right of our employees to voice their personal opinions. The opinions expressed in [Ms. Phipps Soeiro’s letter] were those of the writer, and not a statement on behalf of Cambridge Public Schools. This was not a formal acceptance or rejection of donated books, but a statement of opinion on the meaning of the donation.”

In part of a larger statement to the Register Forum, Emily Houston and Kendall Boninti, two of CRLS’ librarians, said, “A licensed librarian’s expertise in collection, development is also vital in making the library represent the diverse interests, needs, and experiences of the communities that they serve. Cambridge Public School library teachers have the right to add and remove items from the collection and our decisions are guided by the criteria and procedures outlined in the district-wide, School Committee approved selection policy.”

The story has gained national attention, as many Americans were shocked to hear that this hallmark of children’s literature was being criticized. Others commended Ms. Phipps Soeiro’s move.

At CRLS, people have had mixed reactions. Some agree with Ms. Phipps Soeiro that Dr. Seuss’ children’s books have racist illustrations. Senior Summia Mahmud, who attended the Cambridgeport School and who had Ms. Phipps Soeiro as her librarian, says, “If you analyze a few of his books, you can see the racism it promotes, and I don’t find this that surprising because Seuss was most likely a product of his time.” However, Mahmud does not agree with Ms. Phipps Soeiro’s decision to send the books back. She says, “We cannot just limit ourselves to, let’s say, books about anti-racist ideas and be content with that. It’s crucial to expand our minds and challenge the ideas of the things we are not used to in a place such as Cambridge.”

It seems that most people, even if they do not think his children’s books are racist, think that Dr. Seuss’ early political cartoons are. Sophie Gilbert writes in the Atlantic that while as a collection Dr. Seuss’ early cartoons attack anti-semitism, isolationism, nationalism, and racism, “they also have their own flaws, most notably their racist portrayal of both Japanese citizens and Japanese Americans.”

Later in his career, Dr. Seuss apologized for the cartoons, saying they were “hurriedly and embarrassingly drawn” and “full of many snap judgments.”

His biographer and good friend, Richard H. Minear, said in an Atlantic article that Dr. Seuss tried to make up for the cartoons by incorporating social justice issues into his children’s books. Sophomore Annie MacBeth, who has followed this story closely, said, “I’m sure that there’s a way you can interpret anything as racist, but Dr. Seuss is a fixture of literature in this country and all over the world. You can find something wrong in everything—it seems a little crazy to criticize that.”

Heather Nelson, the parent of a child who attends Cambridgeport, commented, “While I can understand [Phipps Soeiro’s] desire to take a stance against the Trump administration, I think the tone and focus of her letter were unproductive.” Nelson continued, saying, “I think it would have been more productive to focus the letter primarily on the needs of vulnerable children at our school, such as children whose families are at risk of deportation, and to suggest ways to help them, rather than focusing on the merits—or lack thereof—of Dr. Seuss books.”

This piece also appears in our October print edition.