How Do We Quarantine Congress?

May 29, 2020

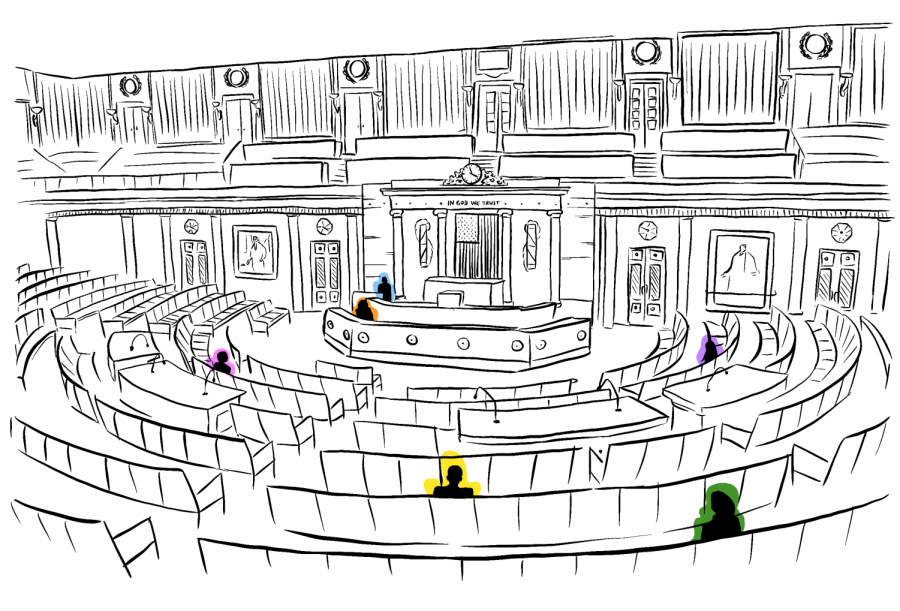

The people of America may be quarantining relentlessly, but what has Congress been doing? How is Congress convening during a pandemic without risking the infection of some of the most central figures in our government? While a general rule holds that members of Congress must be in the House or Senate chamber to vote, this precedent has been debated on multiple occasions. In the aftermath of 9/11, many began questioning the rationality of keeping all of America’s most important legislators in one building during times of crisis. In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, concern about this practice has risen again.

In the Continuity of Government Commission, a report from May 2003 was produced that set a blueprint for how to ensure that the legislative branch is still able to function amidst drastic events, such as a pandemic that could potentially incapacitate enough members to prevent it from operating at all. The primary proposal was to pass a law that would allow for empty seats in the House and Senate to be temporarily filled by appointees. For this law to pass, it would have to be ratified by two-thirds of lawmakers—something quite difficult to do, especially amidst a crisis. Moreover, to cast such votes right now would put lawmakers at risk of infection and could even wipe out Congress. Options such as remote voting, vote-by-mail, and staggered vote timing have been advocated for by senators in the past, but none of these proposals have been approved for reasons that include technological hurdles, complex voter procedures, and possible legal challenges.

Currently, several members of Congress, including representatives Mario Diaz-Balart, Ben McAdams, Mike Kelly, Joe Cunningham, Nydia Velázquez, Neal Dunn, and Senator Rand Paul, have tested positive for the coronavirus and began self quarantining. Regardless, the rest of Congress is still congregating in Washington, filling big rooms and navigating narrow corridors. Even more frightening is the increased risk that many of these members have if they come in contact with the virus. Given that the average age of the Senate is 63, the House is 58, and some of the top leadership entering their eighties, one might see Congress as one of the most vulnerable populations for reasons more than just the offices they hold.

Historically, when a member of Congress becomes incapacitated and unable to fulfill their duties, he or she would go without representation in Congress until the next election, but this means that parts of the country could go unrepresented during important legislative decisions if their congress member dies or is incapacitated. This absence of members due to COVID-19 could give rise to a cloud of illegitimacy over the entire legislative process. Vox imagines a hypothetical situation in which “a large number of Democratic House members are incapacitated while Republicans remain largely unscathed. That could potentially enable a coup, where Republicans replace House Speaker Nancy Pelosi with one of their own and push through legislation that could never pass a Democratic House”. This, of course, could be a nightmare for some and a dream come true for others. Furthermore, a legislative branch that is unable to function at all opens the door for more executive power without consultation with lawmakers, thus imbalancing the branches of government and ultimately leaving the executive departments unchecked.

Although it may seem plausible to have Congress cast votes online, this approach is overlooking the primary function of this body: to share ideas, deliberate, compromise, and build a majority. As John Fortier, the executive director of the Continuity of Government Commission put it, “Congress literally does mean ‘coming together,’ and we forget how much of what takes place requires that. It’s a much more complex place than just pushing a button one way or another on a roll call vote.” Though online participation and temporary stand-ins for incapacitated members are practical solutions to a crisis where it is unsafe or impossible for a full Congress to convene, these institutions are suboptimal and will take time to be implemented. As the Continuity of Government Commission warned, “in the event of a disaster that debilitated Congress, the vacuum could be filled by unilateral executive action—perhaps a benign form of martial law. The country might get by, but at a terrible cost to our democratic institutions.” The risk here, which stands in the event of any crisis, is the potential loss of legitimacy within our government, one of which is so well known for its checks on power and promise of democracy.

Around the world, legislative bodies have been suspended for social distancing efforts. China’s National People’s Congress, whose 2,980 members sit shoulder to shoulder, has been postponed from early March and is looking to resume May 22nd. In Italy, to vote on the increase of deficit spending to tackle the emergency, the heads of parliamentary groups decided that the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate would gather only once a week, and agreed that only half of the members of each House would be in Parliament. This move limits the functioning of Parliament to such an extent that could prove costly and dangerous to democracy. Though it has already proven too late to prevent this crisis from undermining the effectiveness of Congress, hopefully, post-pandemic, politicians can establish a way to ensure that the functions of Congress can be carried out when it is unsafe for members to convene in the close corridors of the State House.