Fighting Deaf Discrimination with American Sign Language

Why Early Exposure to Sign Language Is Critical for Deaf Children’s Acceptance

November 7, 2019

Babies are born without the means for verbal communication. They don’t know how to use spoken words to express themselves, so instead, they resort to headache-inducing cries and shouts. Some parents deal with the tantrums; they try to translate the screams and the grunts and the pointing into comprehensible language. Others look toward different coping mechanisms. They teach their babies American Sign Language, or ASL. They teach only a few simple signs, like “eat,” “more,” or “milk”; signs that can easily be mimicked. Surprisingly, these signing babies are not all deaf. In fact, it is incredibly common for hearing parents of deaf babies to not use sign language with them, but to prioritize verbal communication by forcing their children to undergo speech therapy. Why should hearing babies use sign language, but not deaf babies? It’s nonsensical.

These deaf children, the ones who are forced into the hearing world with no exposure to ASL, experience something called “language deprivation.” According to Patrick Rosenburg, a researcher working with the Language Acquisition and Visual Attention Lab at Boston University, “Language deprivation can have an impact on memory development, on cognitive development, brain developments, and cognitive capacity that make it harder for the child to retain [and] to understand things like mathematical representation and literacy.” As these children grow older, they feel as though they are in between two worlds: not knowing ASL in the deaf world and not being accommodated for in the hearing one.

Matt Hochkeppel, the ASL teacher here at CRLS, was one of those deaf babies. “While growing up, my hearing family left me out,” he told the Register Forum. “I have three brothers, two older and one younger, so four boys altogether. It was chaotic.” Hochkeppel’s parents didn’t learn to sign, and he was mainstreamed into hearing elementary and middle schools, where they didn’t allow him to sign or have an interpreter. Hochkeppel underwent speech therapy, but now only uses ASL. “As I got older, people became more and more communicative, more talkative, but not to me,” Hochkeppel explained. “I wanted to play baseball and basketball, to just play with them, but my friends would talk and my brothers would talk, leaving me out.” Hochkeppel is not alone. As of 2014, 75% of deaf or hard-of-hearing students are mainstreamed into US public schools and half are in special education classrooms.

For high school, Hochkeppel went to the Model Secondary School for the Deaf, located in Washington DC, where he had a much better experience. There, he played soccer and football and was inspired to pursue a career in education.

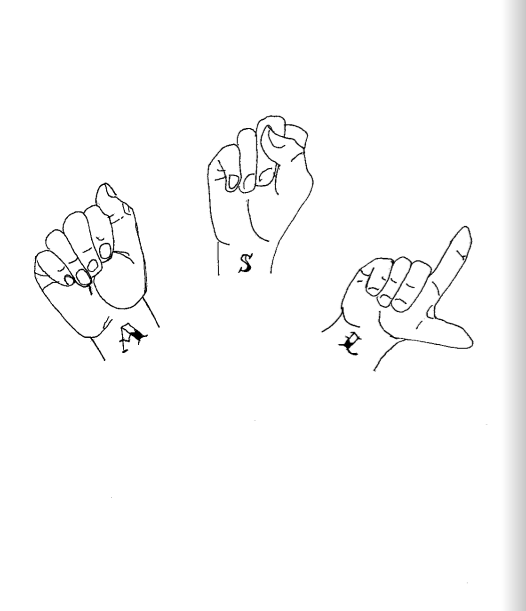

When asked what hearing individuals could do to support the fight against deaf discrimination, Hochkeppel’s response was short and sweet: “Easy—know your ABCs. Know your name. Use gestures, like ‘food’ or ‘drink.’ Easy.” It’s almost anti-climactic, right? But it’s true. These seemingly minuscule changes to your life can have a massive effect on others. Imagine that. One name signed instead of spoken can act as a bridge between two worlds.

This piece also appears in our October 2019 print edition.