Mental Health Awareness Alone Is Not a Solution

May 30, 2018

Around twenty percent of teenagers experience some form of depression before reaching adulthood, and 2016 Teen Health Survey data reported that anxiety and depression rates had increased in the last ten years. While this can manifest in a variety of ways, it is generally agreed that such health issues are not helped by the fact that all teenagers undergo intense pressure and stress throughout high school.

On April 26th, CRLS held assemblies throughout the day to educate students about mental health and help “to reduce stigma associated with mental health issues.” While such goals are laudable, there remains a key disconnect between the problem and the solution. Acknowledging and informing an audience about an issue is important, but these actions in themselves do not directly lead to a resolution. Much in the same way that scientists only studying melting ice does little to affect the issue of climate change explaining the nature of depression and anxiety to unaffected individuals does not remove those conditions from the populace.

These types of attempts to combat poor mental health are not unique to this assembly, or to CRLS at all. This awareness-based approach is widespread, and is just that—focused solely on making awareness of depression and anxiety commonplace. Depression and anxiety are very real disorders, arguably on the same plane as other chronic illnesses. However, they are largely not treated as such. Seeking to purely inform the public takes no great strides to limit the causes of depression and anxiety, which would make little sense in the context of any other health issue. The treatment of Ebola, for instance, was marked by stringent preventative measures combined with research to develop new treatments, not just informational campaigns. Explaining why Ebola was so deadly helped to educate the public and help unaffected individuals avoid infection, but it was research, containment, and the work of doctors that ultimately led to the end of the 2014 outbreak.

While this is a harsh comparison, many of the same ideas apply. Many schools—CRLS included—seek out awareness as the answer to a student body’s depression and anxiety woes, and in some cases, these efforts can be lifesaving; assemblies like the one in April can help a friend recognize the symptoms of a depressed classmate, or a teacher identify a student stricken with anxiety. But after sufferers are identified, then what? In the best-case scenario, those suffering with mental illness readily agree to appointments with a therapist or are prescribed antidepressant medications. Unfortunately, not all patients have equal access to these treatment options, and either way, this approach remains one that regards mental illness as a problem to be quickly resolved, not one to be prevented. Ideally, more extensive, school-based efforts would be taken to prevent depression and anxiety in the first place—a more flexible school schedule, more opportunities for students to relieve stress, and attempts to remove pressure and competition from the academic environment.

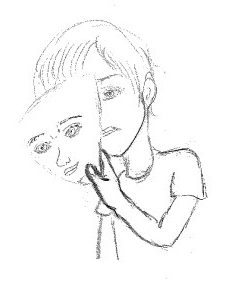

Stress is commonplace today—so commonplace, in fact, that any outward reflection of depression or anxiety is quickly stigmatized as counterproductive by those who cannot relate; such issues have been normalized to the point of ridicule. And our solutions reflect this. We now understand the depth and severity of the issue. We are educated and well aware of the effects and prevalence of mental illness within our society. But the time for education is over. Now, we must move towards solutions.

This piece also appears in our May print edition.