Chocolate and Child Slavery

In Cote d’Ivoire, cocoa farmers make under $2 a day.

November 29, 2018

Despite the fact that Halloween was weeks ago, you may still be sneaking a piece of candy from your waning supply every so often. The plastic-wrapped, sugary morsels collected on the holiday seem to conjure an image of fun, but the underlying reality isn’t nearly as sweet. That chocolate you are mindlessly nibbling on was likely picked by child slaves.

Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire produce around 70% of the world’s chocolate, much of which is bought and distributed by companies such as Nestlé and Hershey’s. In Côte d’Ivoire, cocoa farmers make under $2 a day, resorting to child labor to maintain competitive pricing. In these countries, it is estimated that 1.8 million children are subjected to “the worst forms of child labor,” according to a Tulane University study.

Think about who is truly paying–financially or figuratively–for your chocolate.

Poverty is a major factor in children seeking work, and much of the labor force on cocoa plantations comes from traffickers in surrounding countries, such as Mali and Burkina Faso. Once on the farms, there is no guarantee that these children will see their families soon, if ever again. According to the International Labor Organization in a 2002 survey, there were around 12,000 trafficked children working in Côte d’Ivoire’s cocoa plantations. Twelve thousand.

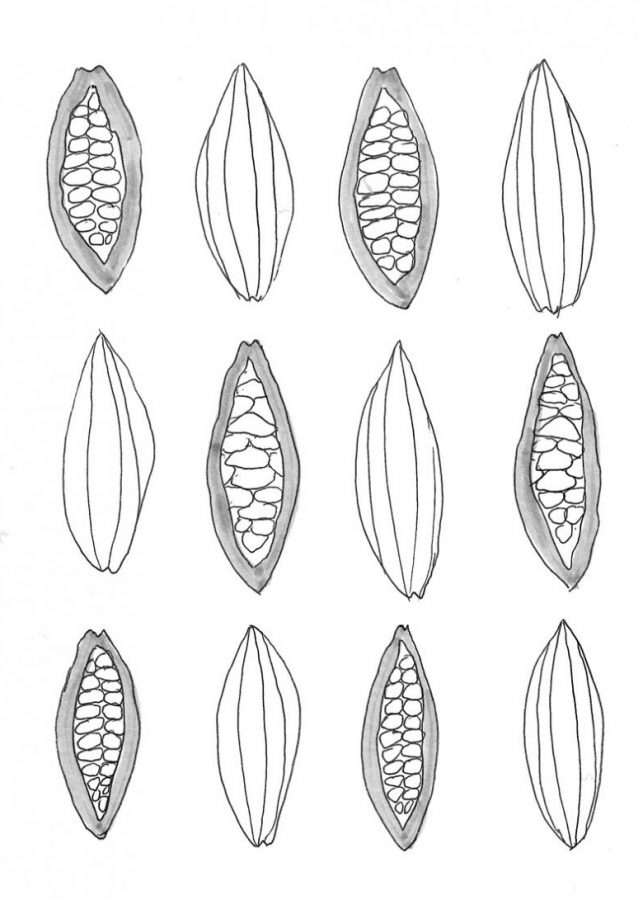

Harvesting cacao is no easy work. Many of these children are between the ages of twelve and sixteen, and their daily work consists of cutting bean pods with large machetes, hauling 100-pound sacks of pods through the forest, and then cracking them open. Because of the hard machete strike that this action requires, many of the children’s hands and arms are marked by deep scars. And since children start work on cocoa plantations so young, their education is limited.

In a 2000 BBC documentary, a boy from Côte d’Ivoire responded to the enjoyment people in the rest of the world obtain from eating the chocolate he produces. “They are enjoying something that I suffered to make,” he said. “They are eating my flesh.”

Major companies who buy this chocolate are taking action to address labor practices, though not in a timely way. In 2001, the Harkin-Engel Protocol was introduced and sought to “eliminate the worst forms of child labor” in cocoa production in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire.

The signers, which included the eight major cocoa companies, two U.S. senators, and the ambassador to Côte d’Ivoire, pledged to meet these goals by 2005, though they failed to meet this deadline. Now, a new declaration to support the implementation of the protocol by 2020 has been signed.

But all of this doesn’t mean you have to give up the chocolate you love so much. Chocolate certified as fair trade almost always mentions it on the label, and in buying it you can know that the producers were adequately paid and no children were involved.

Brands such as Taza, Theo, and Equal Exchange are good fair trade options. Guittard is a personal favorite of mine, because not only is the chocolate fairly sourced, but it is also some of the best that I’ve tried.

In order to address the problem of child labor in cocoa production, we need to be conscious about the issue when buying. In addition to this, larger corporations must take action to ensure better conditions for their farmers. However, anyone can make a difference by voting with their dollar.

Although this may not be the most popular opinion, you don’t need to eat chocolate all the time. Consuming low-quality, sugar-packed, unethically-sourced chocolate often does not compare to savoring a rich, smooth chocolate whose origins you can feel comfortable with. Talk about guilt-free.

I get it. It’s easy to forget (or never even know) about these unjust labor practices, and chocolate is delicious. But now you know. Ethical chocolate is often more expensive, but when considering whether it is worth the price, think about who is truly paying—financially or figuratively—for the other options you may be reaching for. It may not be you, but it is someone. And more often than not, that someone is your age or younger.

This piece also appears in our November 2018 print edition.