Chromebook Policy: Holds Promise, Badly Executed

This year, every CRLS student was provided with a Chromebook for academic use.

September 28, 2018

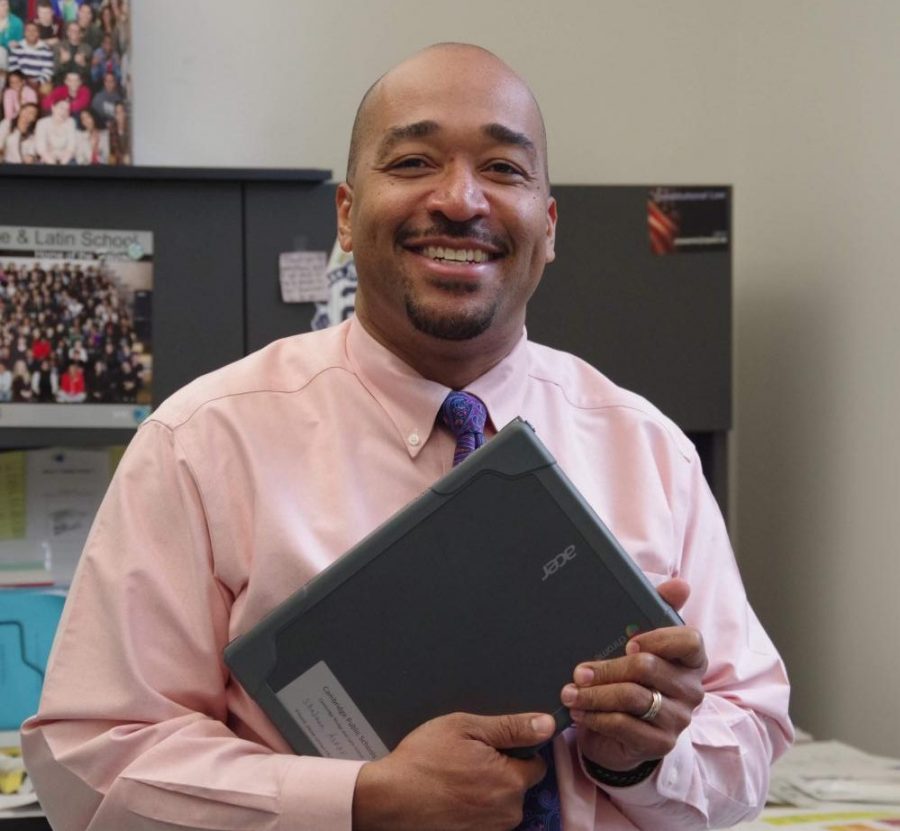

Over the last few years, CRLS has seen gradual shifts in its usage of technology, from the replacement of centralized computer labs with laptop carts in 2017 to the increased integration of G-Suite products like Google Classroom and Gmail. Changes implemented at the start of this school year have taken this one step further, providing every CRLS student with a Chromebook for academic use, inside and outside of school, through the new “CRLS Connects” program.

First distributed to incoming freshmen for the 2017-2018 school year, the Chromebook program was conceived with equity and digital accessibility in mind. On the surface, this transition seemed to be the next logical step; in an increasingly Internet-reliant classroom and a school with a diverse range of income backgrounds, free computers would both expand connectivity within the classroom and improve student’s abilities to complete essays and online assignments outside of school.

But the policy’s execution and the decisions behind it remain flawed. For one, computer science courses (which are increasingly popular at CRLS) require computer systems the Chromebooks cannot provide. For example, the devices have little internal storage and are designed to function merely as “Internet portals” rather than fully-functional devices. Secondly, school officials have enforced the 1:1 policy for all students, meaning that having a Chromebook is no longer optional; the use of personal computers is discouraged, and this is imposed through the removal of publicly accessible Wi-Fi.

On documents signed by students and families during distribution sessions, the replacement fee of the Chromebook and accessories is listed as $348.35—to be paid if the device is damaged or lost. Essentially, families are required to accept the responsibility of Chromebook “ownership,” while simultaneously being prepared to pay for damage to a device they may have had no desire to own in the first place.

In terms of capabilities, Chromebooks are uniquely suited to an educational environment in that their functionality is limited to basic Internet access. However, when it comes to distributing devices meant to replicate the needed experience for those who would be unable to afford laptops, Chromebooks fall short. In the real world, they are rarely the consumer’s first choice, and although higher-end models range from $600-1000 and come with features like touchscreens and styli, the 11” Acer C740 devices the school has purchased do not provide any sophisticated computer skills students may need in competitive job markets. And assuming that each new device and accessory was purchased for the replacement price, the district spent roughly $425,000 to $520,000 on Chromebooks this year alone.

Prior to the introduction of CRLS Connects, students were able to bring in personal computers at any time for work on in-class assignments, when laptop carts or the (since removed) desktops around the building proved inconvenient. Additionally, some without personal or portable computers had access to desktop computers outside of school, and were still able to complete work in this manner. The irony of this situation, therefore, is that students with capable devices are prevented from using them, while taking on the responsibility of a second, school-issued device.

Moreover, low-income families that may have usable devices at home would be hurt the most by a $300 charge—a risk that many would not willingly take on for four years (since Chromebooks remain with students over the summer). In the case of families understandably unwilling to assume responsibility for any device, such students should be able to fully opt out of CRLS Connects, relying on devices at home and in-school laptop carts instead. In short, devices should only be offered to families that both need and request them.

To better tackle the issues with Chromebooks and establish equity between students from a wide variety of economic backgrounds, CPS should instead distribute higher-end computers to students who opt into the program based on demonstrated need. From that point, those devices can remain at home for all four years if the student desires (involving much less risk than bringing a $300 device across the city twice a day), or brought into school to better “level the playing field” in terms of device quality and capabilities; this way, all students could choose to use higher-end computers in class. Alternatively, classroom computer use can continue as it had successfully operated in previous years—with existing laptop carts and library desktops.

This piece also appears in our September 2018 print edition.