As secondary education shifts its focus towards producing specialized workers rather than free-thinking citizens, English and social science departments have increasingly been cast aside amid mounting budget cuts, administrative pressure, and student apathy.

Here in Cambridge, the gap between the humanities and STEM is wide and growing. According to the CPS budget, $168 was spent in the math and science departments for every $100 spent in the English and history departments in 2025, a wider gap than the 2016 ratio of $100 to $146. CRLS currently offers nine AP humanities courses, while twelve college-level math and science courses are available. STEM APs, like calculus or chemistry, also have ample teachers and periods, making them accessible to all students. But as any student in course selection knows, humanities APs are much harder to enroll in due to a lack of teachers and scheduling options.

At the college level, Cambridge’s own Lesley University laid off 30 faculty members and cut degree programs in political science, sociology, and global studies in 2023. At Harvard, concentrations in English, social studies, and history have grown increasingly unpopular, losing ground to programs like computer science, engineering, and applied mathematics, according to the Harvard Undergraduate Open Data Project.

So the question remains: why the gap? Why are both students and administrators choosing to go all in on math, computer science, and chemistry while neglecting English, history, and social studies? The answer lies in a changing view of education—no longer seen as a cultural rite of passage into adulthood but as a direct path to career readiness. Secondary education is not creating free-thinking citizens, but instead skilled and specialized employees, ready for the corporate machine.

In an age of rising tuition costs and an increasingly competitive knowledge economy, parents funnel their kids into STEM fields, hoping they’ll get higher starting salaries and better job security. However, in doing so, society has lost the view of what an education is truly for. The humanities, while lacking the high-paying career options of the STEM fields, have an invaluable influence on the ways we see the world. Without them, we risk reducing education to mere job training, neglecting the critical thinking and ethical reasoning that shape a meaningful society.

But reversing the current trend won’t be easy. First, institutions like colleges and school districts need to stop measuring success using starting salaries and job performance alone. And high schools like CRLS need mandatory, school-wide history and English classes that are rigorous and engaging.

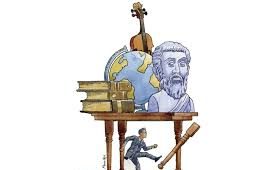

Ultimately, the humanities crisis is not just one of budget cuts and waning interest. It’s about the type of world we want to cultivate and the role of education in that world. If we continue down the STEM-dominant path, we risk creating a future that is technologically advanced but intellectually impoverished. Just as the light dove mistakenly believes flight would be easier without air’s resistance, humanity may soon believe that transcending religion, philosophy, and literature will lead it to a higher plane of existence—only to find that without them, existence has no meaning.