On April 30, 2024, the United States Preventive Services Task Forces (USPSTF) finalized new breast cancer screening policies. In the new policies, women ages from 40 to 74 at an average risk of breast cancer are advised to get screened every two years. The pre-existing policies called for women in their forties to “make an individual decision with their clinician” based on their “health history, preferences, and how they value the different potential benefits and harms.”

These guidelines remain majorly unchanged from last year’s draft, receiving a lot of criticism and concern for “not being enough.” According to Johns Hopkins Medicine, one of the most prestigious medical school programs in the world, a “mammogram every year is recommended” even if your doctor “forgets to mention it.”

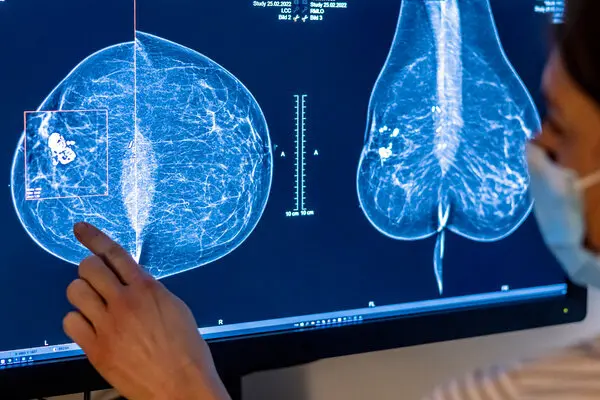

However, the topic of frequent breast cancer screening is a controversial subject in the medical field. Popular points of criticism concern the possibility of misdiagnosis. Some, younger people in particular, tend to have denser breasts, affecting the accuracy of mammograms and often resulting in false positives. With annual screening, the rates of false positives would increase rapidly. NEJM Journal Watch, a series of public medical newsletters, state “computer models suggest that screening biennially instead of annually could lead to a 50% decrease in false positives but a slight increase in breast cancer–related mortality.” While the possibility of discovering breast cancer early seems to outweigh the negatives of receiving a false positive, some studies indicate that false positives increase the likelihood of undergoing invasive surgery—only to discover that there were no tumors to begin with. Another consequence, according to the National Institute of Health, is that false positives increase “short-term anxiety.”

In the U.S., 40% of cancer in women is diagnosed as breast cancer, affecting about 13% of women. Although an annual mammogram screening won’t decrease the risk of developing breast cancer, it will increase the likelihood of detecting malignant breast tumors at an earlier stage. The Journal of American College of Radiology (JACR) writes that “among 559,091 women who participated in screening, there was a statistically significant 41% reduction in breast cancer deaths within 10 years of diagnosis and a 25% reduction in the rate of advanced cancers.” They conclude that “there is risk in not screening; treatment advances are important but cannot overcome the disadvantage of being diagnosed with an advanced-stage tumor.”

Additionally, breast cancer is found to disproportionately affect minority women. The USPSTF finds that “Black women are 40% more likely to die from breast cancer than white women, and too often get aggressive cancers at young ages,” as a result of less access to health care, less access to adequate health care and various lifestyle patterns. So, new policies that urge younger people to get screenings more often may not just only help combat breast cancer as a whole, but actually also help equitable treatment and acknowledgement of minorities.