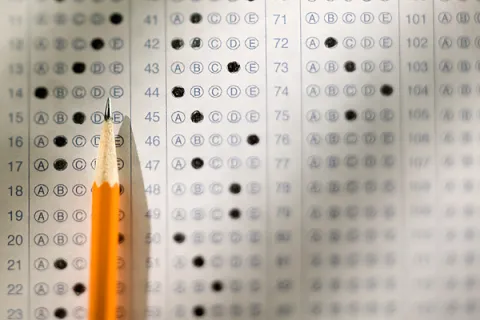

CRLS grading policies have undergone a radical paradigm shift over the past 6 months. School administrators have boldly associated these policy changes with the word ‘equity’, but what is equity and what do these changes accomplish?

Many people know that equity is closely correlated with fairness. This is true in the sense that equity implies impartiality, but the assumption that an equitable system will provide everyone the same resources is incorrect. Equity is not fairness in the sense that everyone will receive the same resources; it is fairness in the sense that everyone will be allocated the necessary resources to reach the same outcome. In the context of a race, every student starts at a different line based on their level of education. Equity is not every student starting at the same time; it is each student starting at different times based on their current position so that they finish at the same time. This distinction, although subtle, provides a glimpse into the minds of school administrators and sheds light on what the new policies really are. Equity in grading is a big problem as it contradicts the fundamental definition of grades. Grades are meant to be a holistic way to show and distinguish student achievement while equity homogenizes them. These two things cannot be juxtaposed.

The Grading for Equity Presentation given during Falcon Block states three things: extra credit and participation grades will be cut from all teachers’ policies, the minimum grade will be raised to 50, and students will be allowed numerous opportunities to revise their work.

The presentation uses the fact that there are more ways to numerically fail (getting an F) than there are to get an A, to justify raising the grading bar to 50. The presentation also cites that the bar of 50 ensures that performing poorly on, or missing an assignment won’t be demoralizing or drag a student’s grade down too much. There is a fallacy in the logical reasoning being presented here: the possibility of getting a grade and the probability of getting a grade are different. One has a higher possibility of getting an F than an A because there are more numbers falling within that category, but they are not necessarily more likely to get an F. Raising the bar to not “demoralize” poorly performing students does not solve the root problem of their poor performance. Instead, this falsely reports their performance by inflating their grade.

The biggest caveat of these changes is that they are inconsistent. The policies are simply guidelines that teachers implement within their individual grading style. A student may be able to revise up to 25 percent of what they lost in one class, while another may be able to revise for full credit. Students may not be graded for participation in one class, whereas students in another may be graded for participation with a rubric in accordance with standards based grading. Individual teachers’ policies should not take precedence over general school policies. This lack of consistency casts doubt as to whether these policies are actually “bias resistant”, and if extra credit needs to be removed for the sake of uniformity.

Grading for Equity is a flawed program by school administration that takes the wrong approach to the problem. Poor reasoning behind radical changes undercut the previously working facets of grading, while the inconsistent execution of the policies is inconsiderate to students. Amidst all this, equity has become a throw-around word used as a crude justification for hasty decisions in the name of impartiality.

This article also appears in our June 2024 print edition.