In Defense of the Offense

The Right to Offend is an Important Part of Society

December 19, 2017

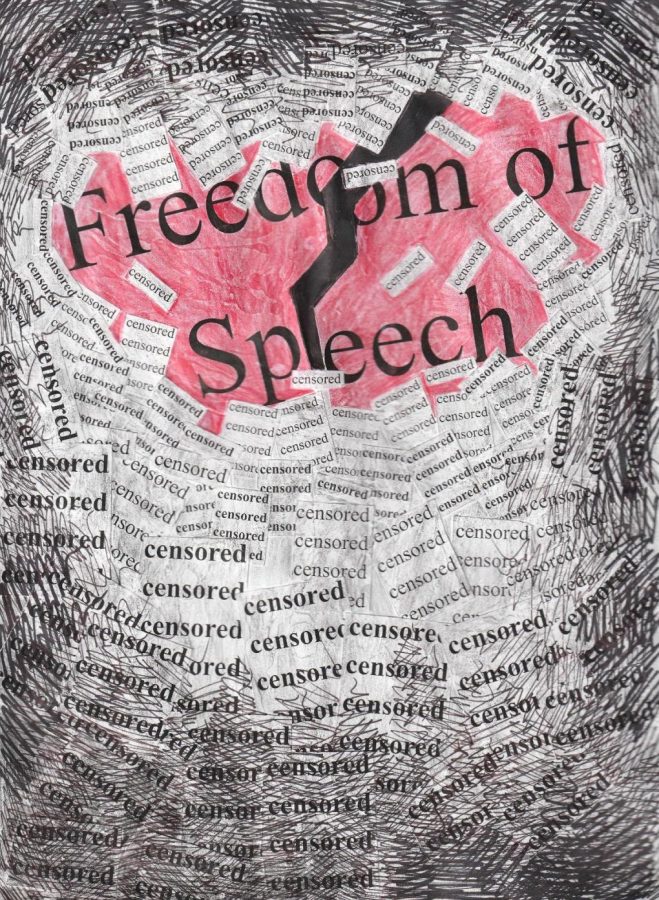

When conversing with fellow CRLS students, I have never encountered opposition to the idea of free speech. No one is willing to say “I don’t like free speech.” What they say instead is, “I am for free speech, but…” or, “You can say what you want, but don’t offend.” Many CRLS students don’t like censorship, yet they’re not comfortable with speech that offends or provokes. The right to offend is not an add-on to freedom of speech—it lies at its very core.

Since the 2016 election, I have sensed a growing culture at CRLS that says it is wrong to offend. In this culture, students accept and even demand constrictions on freedom of speech in the name of respect and tolerance.

CRLS has a quote cased in a staircase near the library on the second floor from author Salman Rushdie that perfectly states the trouble with this tendency: “What is freedom of expression? Without freedom to offend, it ceases to exist.”

In a community like CRLS, offending someone is both inevitable and often important. That is because it’s far better to have clashes of deeply held views in the open and to try to resolve them in the open than to repress them in the name of respect or tolerance. It’s true that such a debate at CRLS may bring into the open speech that is injurious, especially to vulnerable communities. But the right to offend is important because any form of social change or progress involves offending some deeply held sensibility. “You can’t say that” is all too often the response of those with power when their power is challenged.

If we say there are certain things that can’t be said, what we’re saying is that there are forms of power that can’t be challenged.

Censoring free speech in order to challenge bigotry may seem like a good idea on the surface, but it raises one big question: Who gets to decide what is to be censored? Just a few years ago, Charlie Hebdo, a satirical French newspaper, published pictures of Mohammed the prophet, which is very offensive to Muslims. Iqbal Sacranie, the head of the Muslim council in Britain, wanted the cartoonists to be prosecuted for offending Muslims.

But a few years before the cartoons were drawn, he made derogatory comments about homosexuality on national radio. He thought he was expressing the Islamic view on the matter. But many gay groups were offended, leading to a hate speech investigation by the police. This shows that limiting the free speech movement is very dangerous.

When you try limit someone else’s free speech, you might end up limiting your own. Those in power like to state something along the lines of, “My speech should be free, but yours is too costly.” If we limit the right to offend, we limit the right to offend power and, ultimately, the right to speak.

This piece also appears in our December print edition.