*This article contains topics of eating disorders that may be triggering for some readers.*

The bike path seems to stretch on forever we think to ourselves, just the quiet sound of our feet pounding the pavement, the occasional leaf crunching on impact. The first mile feels easy, adrenaline pumping us along, the cold air not yet stinging too sharply. We run side by side, our bodies in silent communication with each other, pushing ourselves down the path.

We wind endlessly through the quiet residential neighborhoods, running in the middle of the empty street, only our heavy breathing filling the air. We run past playgrounds and churches, pass stores and apartment buildings, and get a small glimpse into others’ lives. Our pace slows as fatigue catches up, our fingers curled into small balls to preserve what little warmth is left in them. As we round the last bend of our run, a sense of accomplishment pours over us, and a warmth fills our bodies back up, as joy and adrenaline carry us home.

Runs like these are normal for girls on the CRLS Cross Country team, they are constantly exploring new parts of the state, covering an average of 30+ miles each week. This team truly knows the importance of teamwork, as Eliza Dickie, a CRLS Senior and Varsity Girls Cross Country Captain puts it, “Being able to run with the team every day is amazing because it turns something that would otherwise be a challenge into something to look forward to. I’ve had some of the best conversations on long group runs and it builds trust and community so quickly.”

Sports like Cross Country are so important for many reasons, a fact not often disputed, but for girls, the reasons sports are so key lie deeper than just general health and well-being. The skills girls are equipped with by having positive experiences with sports, such as confidence, leadership, and teamwork, can make a lasting impact.

Sports teams can offer a safe space for girls to learn key life skills that instantly propel them forward in life. Meadbh Keane, a CRLS senior and Girls’ Varsity Soccer Captain, who participated in many activities throughout her youth in Cambridge, feels that the sports she has done have helped her become the person she is today. As she says, “It gave me a safe space to express myself with people who relate to me.”

Girls’ sports, however, come with their fair share of problems that are talked about a lot less than they should be. One of the most crucial issues to discuss is the dropout rate of girls in athletics by the time they reach high school age.

The push and opportunities for girls’ sports start off strong for younger girls. With a large abundance of youth sports programs available for girls across the country, it is no surprise so many are involved. With less homework and fewer responsibilities, girls all over flock to the soccer pitch and dance studio after school to make friends and be active. CRLS Senior, Nova Johnson says, “Doing an after-school sport in elementary and middle school was a great way to not only get outside but to also make new friends.”

However, as these athletes grow older, more and more begin to drop out of sports. According to the Women’s Sports Foundation, “By age 14, girls are dropping out of sports two times more than their male counterparts.”

Age 14, the time most girls reach high school age, is when, in some people’s opinions, sports become more enjoyable. As Juliette Coley, a CRLS Senior and member of CRLS Track and Field and Varsity Girls Soccer says, high school sports have been more consistent than youth and have taught her discipline which has given her a stronger sense of community. She can work harder and play harder and see the results of her effort pay off, for example when she helped her relay team make it to New Balance Outdoor Nationals in the spring of last year.

A survey was conducted over the first week in January to get thoughts and opinions from CRLS students and staff on girls’ sports in Cambridge. 50 responses were gathered, covering a diverse range of backgrounds and identities. With 82% of the responses coming from individuals who currently or have in the past, participated in girls’ sports in Cambridge, many respondents were able to approach these questions with their personal experiences.

When presented with the statistics of the girls’ sports dropout rate, the majority of respondents of this survey felt outraged, not a surprise as this statistic is almost hard to imagine. This statistic, it should be noted, comes from national data, not in Cambridge specifically, and it is harder for individuals to comprehend this data as we see less of a drastic drop-off in this city.

The jarring statistic of the girls’ sports dropout rate was presented to respondents with the following question, “These dropout rates are due to many reasons, which of the following do you think affects girls’ sports most in Cambridge?” 62% said that one of the reasons was “Lack of opportunity/fewer resources for girls sports.” This is significant because this means that the respondents, all of whom are involved in the Cambridge Public Schools, are seeing a lack of opportunity for girls in sports once they reach a higher age.

Surprisingly, half of the respondents also cited “Lack of a positive female role model,” as another main reason girls are dropping out of sports.

While not often thought of, role models are a key factor in girls’ sports success stories. Having a positive female role model in sport, someone who has similar experiences and a shared set of interests can help girls feel more confident and motivated. A role model is a person looked to by others as an example and is not an easy person to find. Role models carry admirable personality traits such as positivity, humility, and integrity, and being able to have a coach who can be this role model, feels almost one in a million.

Christina Korn is a CRLS Senior and member of the Varsity Girls Lacrosse team, like so many on her team, she sees her Lacrosse coach, Coach Amory, as an inspirational positive role model. Christina states “Coach Amory empowers us to use our voices, she shows us that our voice matters.” Coach Amory is able to be a role model to the team, drawing upon her story of perseverance as she made her way to the World Cup Championship team in Lacrosse, for inspiration in her coaching.

For my writing, I was lucky enough to sit down with Kara Brown, one of the CRLS Athletic Trainers, and discuss many topics regarding female athletics. She has worked as an athletic trainer for over 30 years and has an immense amount of knowledge on sports and health.

When asked about the vital role positive female role models have on girls athletics, Kara cited her personal experience, wishing she had brought her daughter to more female basketball games, “even if she didn’t play basketball, just to have those role models in her frame of mind, rather than the men, which you think about.” She also cites her youth, when not outside playing, she would spend time reading autobiographies of female athletes, seeing these stars as inspiration.

Girls’ sports have been handed their fair share of problems throughout the decades. From pay gaps in male and female professional athletes to lack of funding or media attention, success in female sports has never been a given. However, girls sports got an exponential boost from Title IX, in 1972. Title IX is a law that prohibits discrimination based on sex, gender identity, or sexual orientation, in any educational program or identity for receiving federal financial assistance.

In the case of athletics, schools must provide equal opportunities for male and female athletes, and provide the teams an equal amount of funding. Title IX is so important for giving more girls the opportunity to participate in the life-changing experience of athletics.

While it cannot be denied that girls’ sports would not be where they are without Title IX, some argue that the law is not doing enough for female sports, or that the entire system needs to be reinvented. In her New York Times opinion piece titled, “We Can Do Better Than Title IX,” Lindsay Crouse makes the argument that a more “female-first” approach needs to be taken to make a total reinvention of women’s sports.

She cites the science that male and female anatomy are different, writing, “Like so much in our culture, sports are still based on a male model — a man’s body, a man’s interests. Current models of success in mainstream sport leave women competing on standards that exclude us, where in most cases we are not set up to thrive.”

She says a new system would need to be built around female anatomy and data on how the female body works. In her proposed system, things that seem like minor changes would have a real effect on female athletes. Her system would see pregnancy not as a career ender, as is now often seen by the current elite athlete system. Her system would have a focus on female leadership as she also understands the importance of positive female role models.

Her arguments are backed up by another opinion piece, this one written in TIME by Lauren Fleshmen titled “Sports Were Never Designed Around the Female Body.” Lauren Fleshmen, a decorated American distance runner claims that the sports women fought so hard to be a part of are harmful to them.

She claims that “The sports institutions we fought to gain access to were designed by men for men and boys, and the system is built around physiology and performance norms for male bodies aged 14 to 22.”

While not outwardly stated, Fleshmen seems to agree that a female-first approach needs to be taken. She writes that “If women and girls were placed in sporting environments built around the norms of female puberty and female improvement trajectories if their bodies were respected and encouraged to develop in their own time, outcomes for women would be entirely different.”

The final problem in girls’ sports that must be addressed is health. While not often disputed, participating in athletics is beneficial for adolescents’ health. According to research from the Sports Medicine Division, those who did not participate in collegiate athletics had less mobility and more anxiety. As well as data from the Women’s Sports Foundation citing, “Girls active in sports during adolescence and young adulthood are 20% less likely to get breast cancer later in life.”

Although there is a large array of health benefits, there are less talked about health risks that participation in athletics can pose to females. Often thrown around as a buzzword associated with female athletics, eating disorders, and related conditions are real problems that affect many girls in sports.

One of these related conditions that my research became very focused on is RED-S. Short for Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport, and sometimes referred to as the Female Athlete Triad, RED-S is the continuum of three different health problems.

The first is energy availability, related to disordered eating, this is the condition most are familiar with. Boston Children’s Hospital’s information site about RED-S states that female athletes involved with sports that emphasize leanness, like ballet, gymnastics, figure skating, lightweight rowing, and running—are at risk for developing eating disorders because of pressures to maintain low body weight, or because of poor guidance about nutrition and weight loss.”

The second aspect of the triad is Amenorrhea, or the lack of menstrual period, is when female athletes stop getting their periods due to over-exercising, extra stress or not getting enough good nutrition. As one student said, “My best friend growing up did competitive gymnastics and she didn’t have a regular period until she was nearing 18.” While in the short term for many athletes this can feel like a blessing, not getting your period is dangerous and can have lasting effects such as making it harder to become pregnant.

The last piece of the triad is bone health. The Boston Children’s Hospital cites the dangers weight-bearing sports, such as runnin

g, have on bone development, and that without proper training and nutrition, bone-related injuries are much more common.

In a study conducted by the National Institute of Health, “a total of 192 national athletes responded to an online survey regarding the RED-S risk. Most athletes (67.2%) were classified as having a medium/high RED-S risk.”

When asked about RED-S and related conditions, the CRLS Athletic trainer Kara Brown said she had not heard about it until recently when she attended a seminar about RED-S at Harvard. Before it had just been “anorexia and bulimia,” she says, “RED-S was a kind of a different way of looking at it. And I think sometimes it takes away from that stereotype of just girls and kind of looking in a more holistic way. So that’s one thing that I plan to kind of start using in my practice.”

Unfortunately, it is not surprising that she had not heard of RED-S before, it was only in 2014 when the International Olympic Committee officially recognized RED-S as a condition, sending it slowly trickling down the chain of command to end up in athletic trainers’ radar.

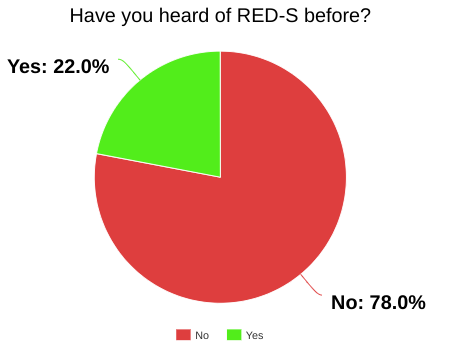

In the conducted survey, when presented with definitions and data regarding RED-S and other similar conditions, and their effect on female athletes, 78% of respondents said they had never heard of this condition before. This significantly adds to the argument that more needs to be done to raise awareness of RED-S and create a change in girls’ sports culture.

A sports culture shift needs to happen, and the importance of it is abundantly clear, 94% of survey respondents selected yes, there should be more done to raise awareness about conditions like RED-S, and that a different girls’ sports culture needs to be created.

Some students offer suggestions about what that new sports culture could look like, and most of it stems from more education. Amy Zhou, CRLS Senior and Ultimate Frisbee player, suggests challenging societal standards in our “size-conscious” world.

As CRLS Senior Sofia Castaldi says, “In general, eliminating discussion of people’s bodies where unnecessary. Focus on athletic performance, not the appearance or build of someone’s body. Educate girls on the importance of proper nutrition, fueling their bodies, and ways to deal with menstruation while doing sports.”

Another way of breaking these barriers to sport is a simple sports bra, which can make the difference for someone considering joining a sports team.

Now comes the “so what?” What can be done to ‘fix’ girls’ sports, is a total re-invention of the country’s athletic system possible? Would it be able to allow girls of all races, ethnicities, and backgrounds to participate? What about the rest of the world, where some countries don’t allow young girls to participate in athletics? And what about trans-athletes, how can they fit into the future of sports?

Many questions seem to constantly be raised in a system where the future of girls’ sports seems to take steps forward, while simultaneously taking a few steps back. But one thing is certain, it is imperative for young girls to constantly keep fighting in the world of sports because they are the ones that can make real change for the future.

This article also appears in our January 2024 print edition.