Now, let’s start by posing a question: How and why did race become so embedded in the every day—and the ordinary—aspects of school and daily life?

On the surface, extracurricular activities appear to create a level playing field, with the idea that anyone can participate in clubs or sign up for activities. However, the persistent dominance of certain clubs by predominantly white student populations raises questions about access, opportunity, and historical legacies. A closer examination reveals an interplay of socio-economic factors, historical exclusion, and deeply rooted socialization patterns. From disparities in leadership roles and honors to the influence of community-based socialization, CRLS is struggling to truly challenge and transform the conventional understanding of inclusivity within certain educational spheres.

“I think that, systemically, clubs themselves and any sort of activities that require an extra amount of time outside of school are just gonna be favorable towards a certain demographic of people that usually doesn’t include people of color,” recounts Elaine Wen ’24, leader of the Model UN Club, one of the largest and predominantly white clubs at CRLS. “There is a stigma surrounding certain clubs like Model United Nations that require more time, especially more money, to be a part of, and that deters a lot of people from joining, understandably so.” She goes on, telling the Register Forum, “I think that CRLS doesn’t do enough, and the leaders of these clubs, myself included, should be doing more to intentionally make sure these environments are welcoming.”

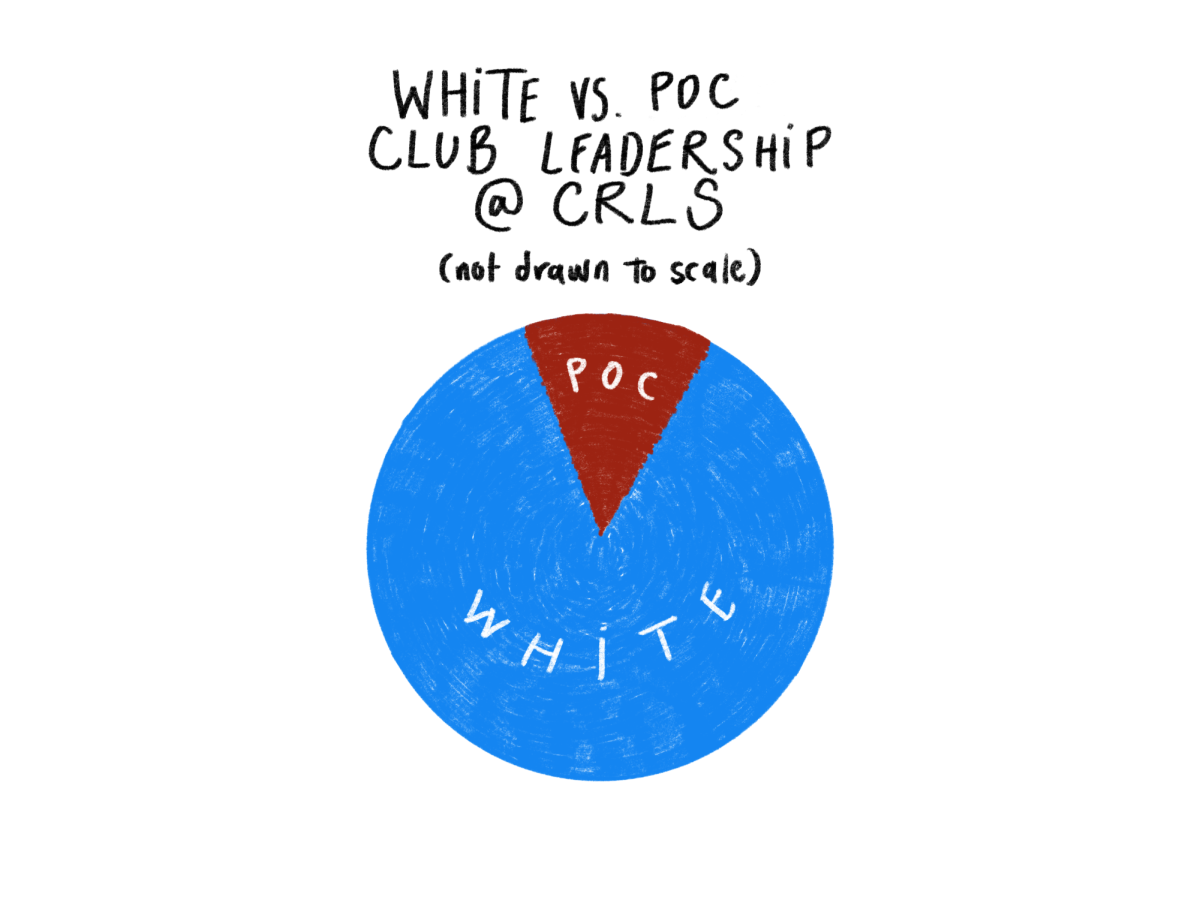

Analyzing data within the same high school, black students reported fewer top-level leadership roles than their white peers, even among academically similar students.

Previous CRLS student Ekram Shemsu told the Register Forum, “The absence of diverse leadership within school clubs can contribute to these white spaces. When students don’t see individuals who look like them in leadership roles, they may be less inclined to join these clubs.” Helen Kidanemarian ’23 adds, “Although in high school I was able to obtain numerous leadership positions, I can say that many students were discouraged [from] applying for leadership or even attending clubs due to the particularly white atmosphere.”

“At Rindge, we don’t like to say it but it’s an incredibly segregated school,” Jeremiah Barron ’24 states. Barron is Editor-in-Chief of the Register Forum and has previously written about a lack of racial diversity within the club. “It’s an issue deeply rooted in American society that black students do not get the same support from white teachers or administrators. So when it comes to joining clubs that have a more educational aspect to them, black students don’t have the support that white students do.”

Both Wen and Barron refer to it as a self-perpetuating cycle, with club demographics forming around initial composition bias and accessibility, which then results in limited representation and thus makes certain students feel less inclined to join. Over time, the cultural and social dynamics of a club further solidify around racial socialization and consolidate leadership in the hands of the same people.

As two black students heavily involved in CRLS extracurriculars, we can provide a firsthand account of the feeling of alienation that can often come with it. It’s like stepping into a room where you’re acutely aware of standing out. The dynamics feel different: conversations, shared interests, and even the subtle nuances of social interactions can feel like a glaring reminder of your differences. We know that there’s no way to solve this problem overnight, but the first step is acknowledging racial power dynamics within school clubs and the disadvantage that it puts on non-white students. Several decades of antidiscrimination and diversity policies aimed at equalizing opportunity have done little to alter the overall distribution of organizational power. Such policies, while helpful, fail to address the racial hierarchies historically built into American schools. Rather than asking how to bring diversity into CRLS clubs, a more apt starting question is why so much power and organizational authority remain in white hands.

This article also appears in our January 2024 print edition.