In their seminal work titled “The Race to Innocence: Confronting Hierarchical Relationships Among Women,” Mary Louise and Sherene Razack, professors from the University of Minnesota and the University of Toronto, introduce the notion of a “race to innocence.” Published in 1998, the piece is a critical analysis of feminist political solidarity, highlighting its failures due to what the authors term as “competing marginalities.” This phenomenon arises when women, in an attempt to distance themselves from guilt or complicity, emphasize their own experiences of marginalization without acknowledging their role in the subordination of other women. By asserting that their own plight is the most urgent, women avoid confronting the existing hierarchies within their ranks. This refusal to analyze one’s complicity in the lives of other women leads to a harmful cycle that further perpetuates oppressive patriarchal practices.

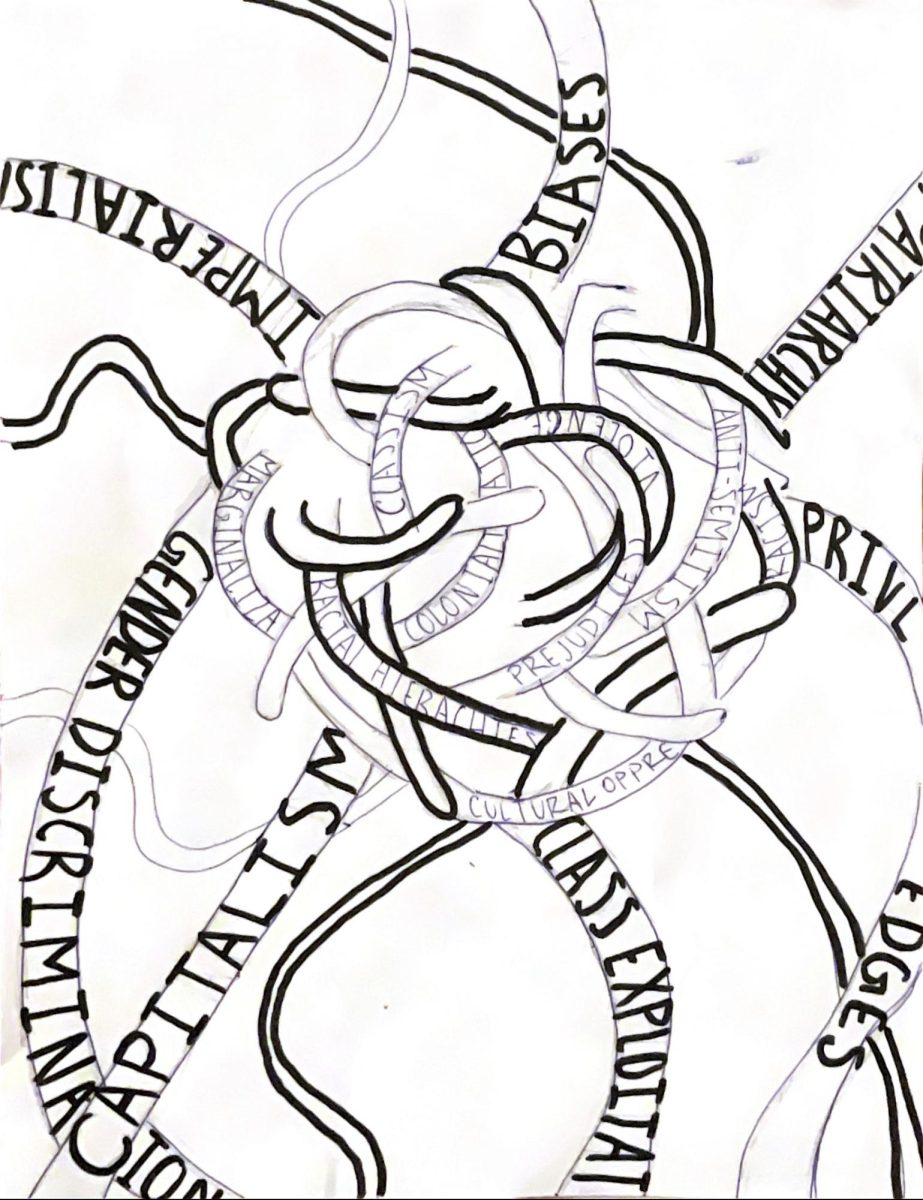

The authors argue that any approach rooted in this “race to innocence” is inherently flawed because it overlooks the intersectionality of hierarchical systems such as capitalism, imperialism, and patriarchy. These systems mutually reinforce each other, forming an interlocking web where class exploitation, gender discrimination, and racial hierarchies are deeply intertwined. Understanding these relationships is crucial for devising effective feminist theories and strategies, as it necessitates acknowledging the intertwined nature of various forms of oppression.

The authors delve into their motivations behind crafting the article, drawing inspiration from a particular failed feminist conference experience. They draw on references to the event, which had to be cut short because productive dialogue was sorely lacking and there was disagreement about what should be discussed first. By grounding their analysis in tangible events, Louise and Razack demystify the complexities of their argument. This approach not only elucidates their points but also engages the reader emotionally.

They argue persuasively that this myopic focus on personal victimhood not only undermines collective progress but also perpetuates the very systems of oppression feminists aim to dismantle. We are forced to confront the uncomfortable truth: our liberation as women is intrinsically linked to dismantling all oppressive systems simultaneously. In reviewing their analysis, it becomes evident that a shift in feminist discourse is imperative. Acknowledging the interconnectedness of oppression does not diminish the validity of personal struggles; instead, it enriches our understanding of the matrix of power dynamics.

The authors’ critique serves as a reminder of the importance of self-reflection within feminist activism. To challenge the “race to innocence,” we must confront our biases, prejudices, and privileges. This collective self-awareness can transform feminist movements into inclusive platforms where diverse voices are not just heard but actively incorporated into the struggle for equality.

Louises’ and Razacks’ exploration of the “race to innocence” provides a perspective that is both enlightening and challenging. I found that, while the term focuses on feminist discourse, its implications are remarkably applicable to discussions on race and queerness and it revealed to me a common thread of struggle. It’s a compelling read for both academics and general readers alike.