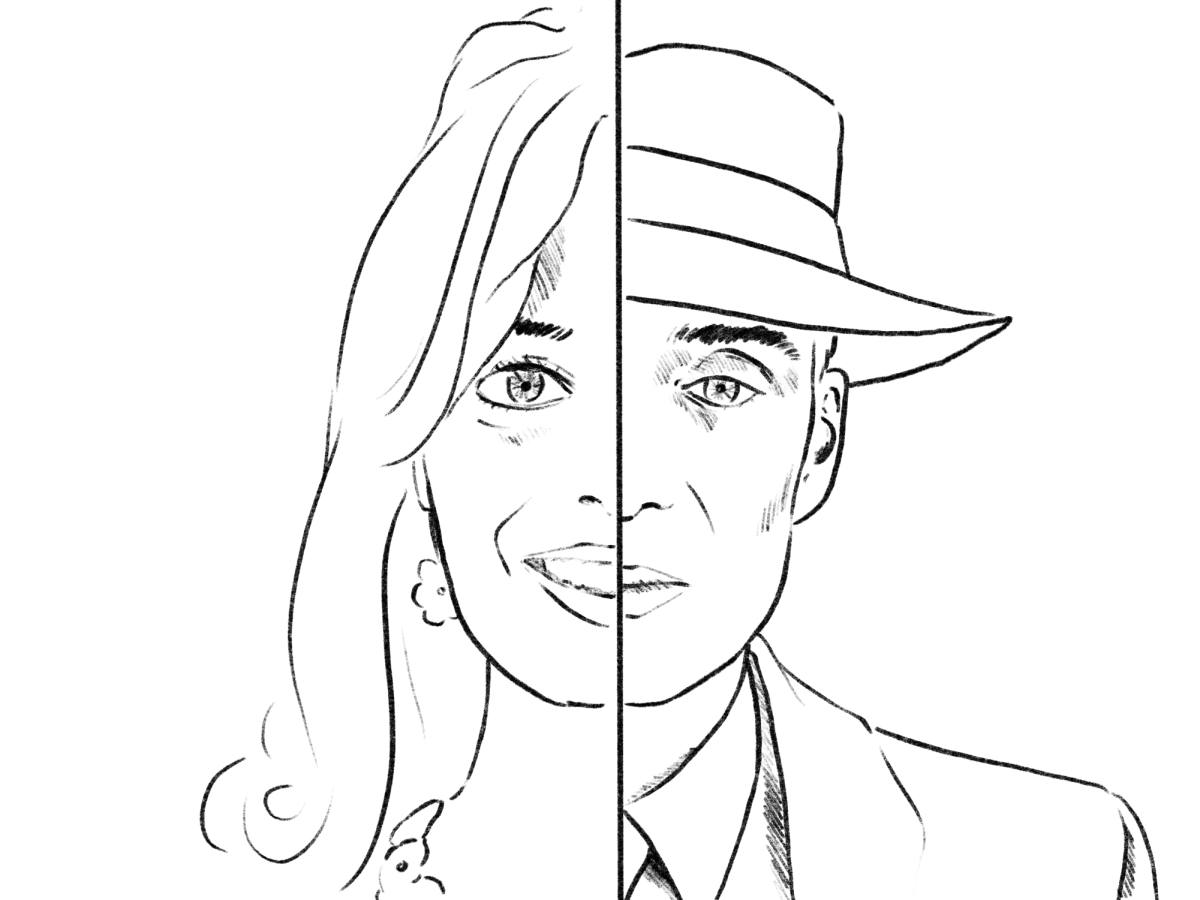

When it was publicized that Greta Gerwig’s Barbie and Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer had the same release date, no one expected the films to grow as a pairing. “Barbenheimer” quickly exploded into a cultural phenomenon prompting audiences to watch the two films as a double feature. But the films seemingly couldn’t be more different. Barbie is childhood memorabilia, and the movie displays that status not only with its glittery reflections on girlhood and almost cartoonish screenplay but also with its PG-13 rating, catering to an audience who would have played with the dolls. Oppenheimer, however, is rated R and features the development and use of weapons of mass destruction and full nudity. While both movies prompt the viewer to reflect on the past as a way of discussing current society, Barbie is intended to be lighthearted and enjoyable, whereas Oppenheimer leaves a feeling of both unsettlement and wonder. However, a major criticism of both films has centered around the feminist perspective. In Barbie, it is the question of white feminism, while in Oppenheimer, it is the lack of female characterization and failure of the Bechdel Test.

The white feminist feel in Barbie is no surprise to viewers, as “Stereotypical Barbie” (white, blonde, skinny, able-bodied, and cisgendered) is the main character. Any struggles she experiences or feminist advances she makes exist in the context of her privileged position in a protected society and therefore can come across as preachy. However, this is called out within the

film. Supporting character Sasha criticized both “Stereotypical Barbie’’ for that same white feminism and the Barbie manufacturer for having a negative impact on women. In fact, both Sasha and her mother are integral Latina characters who shape the film’s message as an intersectional female experience. For a film that had to be palatable and approved by Mattel, it checked quite a few boxes, including calling out incel culture, weaponized male incompetence, the burden women of color face in the context of social justice and change, and white saviorism. Not too bad for a movie not designed to be radical.

Oppenheimer, however, is not made to be a feminist piece but rather depicts historical events. The few and far between female characters featured in the film are surface-level, and exist either for the plot or the fantasy. While Nolan seems to take issue with fleshing out his female characters, he has no problem displaying their flesh in its entirety. Therefore, it is nota shock that the film fails the Bechdel Test, so the real question becomes, should we expect it to? (Passing the Bechdel Test would mean that two female characters had a conversation about anything but a man.) Oppenheimer is based on true events and centers around a man working on a male-dominated project. Is Nolan to blame for choosing to exclude female narratives, or is America to blame for historically failing to document women and people of color’s contributions, if not cutting them out of those spaces entirely? This is not to excuse Nolan, who should have tried harder to include female stories, but perhaps to explain it. There is little doubt about Christopher Nolan’s talent as a filmmaker and his ability to produce thought-provoking blockbusters. But it does make you think—who is the industry continuously giving voice to and who is it not?

This article also appears in our September 2023 print edition.