The Case for Rom-Coms

March 14, 2023

Hollywood has created a completely oversaturated market of heteronormative, overly sexual, and just generally unrealistic movies deemed romantic comedies, or ‘rom-coms’. The genre has forever changed the culture of how society operates, what we think is ‘normal’, how much we prioritize love, and the binary conception of what love looks like.

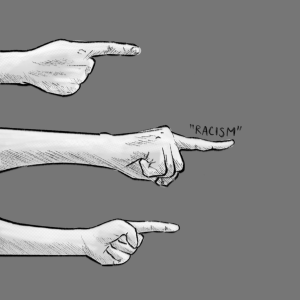

Spanning over decades, the rom-com genre has always been widely popular, but has recently declined in viewership and gross sales. In 2001, 18% of all grossing films were categorized as rom-coms. In 2017, the rate dropped to 5%. The 1990s to early 2000s generated hits like When Harry Met Sally… (1989), 10 Things I Hate About You (1999), Notting Hill (1999), My Big Fat Greek Wedding (2002), and more. However, more recent rom-coms follow the same tired tropes of a crazy, loveless, and obsessive woman, a gay best friend, the romanticization of toxic boundary crossing, shallow makeover montages (the removal of glasses), or the mere existence of the ‘manic pixie dream girl’. Many of these clichés follow existing formulas that only perpetuate rape culture and causal misogyny, uphold gender norms, and just generally capitalize off of women’s insecurities. Beyond sexist themes, these films have historically been exclusively white, or have become spaces of fetishization that have furthered the idea that love is a privilege, only possible for privileged groups: white men, white women, heterosexuals, and rich people.

Once more diverse production teams pitch stories that include underrepresented and excluded groups and intersectional identities, it will result in refreshing and validating media that truly empower these former groups. Shifting this culture seems virtually impossible until we can look at who is responsible for creating the current culture, and actively change what we believe is possible for excluded groups like BIPOC, LGBT+, disabled, and poor communities. Though representing these groups will not solve systemic and structural oppression, love consumes the entirety of our psyches. When we target this sector, we completely change the nature of their health, safety, and esteem. Though this approach may not be an entirely effective solution since there is simply too much to consider, addressing these issues in a pervasive genre of media is ultimately vital in ensuring the mental health, well being, and affirmation of discouraged and abused groups.

Once we see ourselves represented in truthful and honest depictions of love, our internalized idea that we are unworthy and undesirable because of our identity shifts and lessens. The belief that these undermined groups wholeheartedly deserve to enjoy their lives and look forward to universal experience despite the horrific systems that are constantly in effect keeps them hopeful, and even alive. As Phoebe Waller-Bridges’ show Fleabag says in S2E6, “It takes strength to know what’s right. And love isn’t something that weak people do.”

This article also appears in our February 2023 print edition.