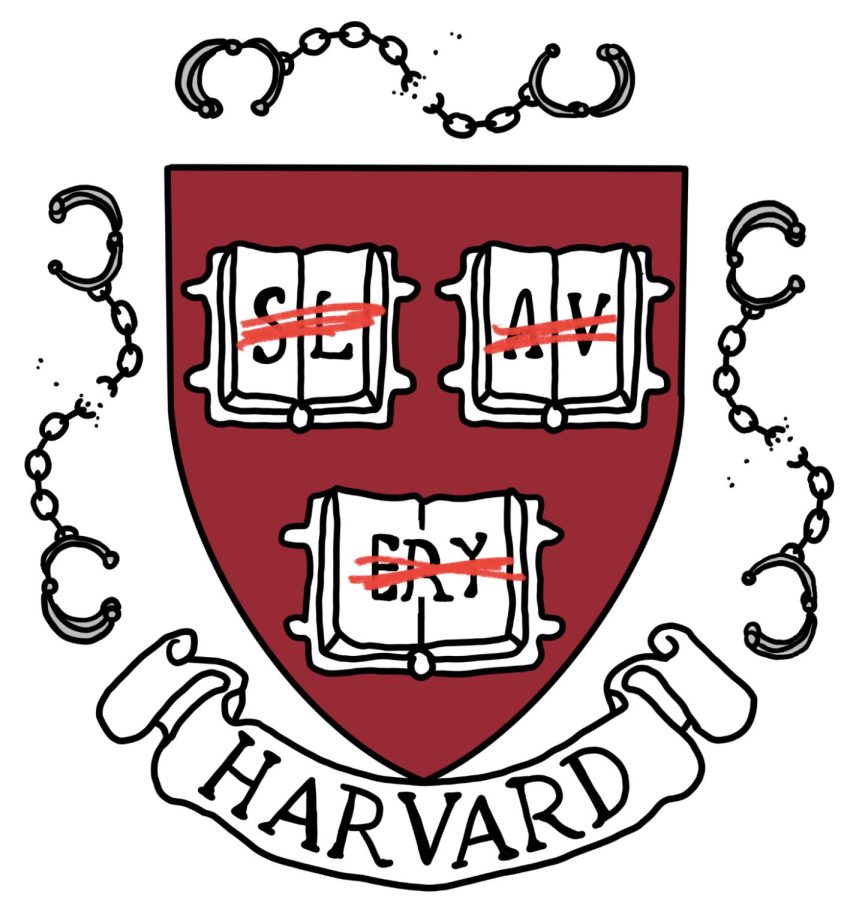

Harvard Report Details an Extensive Legacy of Slavery

June 6, 2022

On April 26, Harvard published a full report on the history of slavery at the university. Running over 134 pages, the document is accompanied by a dedicated website, a short film, and several future commitments—most notably the establishment of a $100 million fund meant to tackle Harvard’s ties to slavery.

Conducted mainly by Harvard faculty members, the study took almost three years to complete. It details how both Harvard’s history and its present-day standing are inextricably linked to slavery, beginning with over seventy enslaved people connected to Harvard and extending to lingering systemic racism. The research further examines facets such as professors’ role in promoting racist ideas and pseudoscience, the immense financial gains from slavery, Harvard’s exploitation of Indigenous people, and Black resistance at the university. It also contains an appendix listing the dozens of people enslaved by “prominent Harvard affiliates.”

Harvard would not have become the prestigious organization it is today without depending on slavery.

An overarching theme throughout the report is that Harvard would not have become the prestigious organization it is today without depending on slavery. According to the paper, “During the first half of the 19th century, more than a third of the money donated or promised to Harvard by private individuals came from just five men who made their fortunes from slavery and slave-produced commodities.”

The report additionally states that, “These donors helped the University build a national reputation, hire faculty, support students, grow its collections, expand its physical footprint, and develop its infrastructure.” Many of these same men are today honored across campus through memorials such as buildings or statues.

The report concludes with seven recommendations for how Harvard can engage with this past and make reparations. These include creating a prominent memorial to those who were enslaved at the campus, funding partnerships with historically Black universities, supporting scholarship on the stories of Black and Indigenous people at Harvard, and expanding partnerships with nonprofits that primarily serve people of color. In a community-wide email, Harvard president Lawrence Bacow accepted every proposal, writing, “I believe we bear a moral responsibility to do what we can to address the persistent corrosive effects of those historical practices on individuals, on Harvard, and on our society.”

CRLS student Birikti Kahsai ’23, vice-president of Political Awareness Club, shared her thoughts with the Register Forum: “It’s a good step to acknowledge the history, but present-day actions are also important. So partnering with HBCUs [historically Black colleges and universities] is great, but they should do more within the actual Cambridge community, and work towards finding descendants. They are still accruing benefits from this.” Nasra Samater ’22, secretary of the Black Student Union, felt similarly, “It truly is the bare minimum—the auctioning of Black individuals is what is allowing Harvard to prosper. As far as what they could do to change, I believe the voices of Black Harvard students and even Black Cambridge residents should be considered in major decisions. These choices directly affect them.”

Roberta Wolff, a Massachusetts resident, learned from the research that two of her ancestors were enslaved at the Henry Longfellow House at Harvard. Speaking to the Associated Press, she said, “If I ever get a chance to speak to the president of Harvard University, I would say, ‘Thank you for the recognition—and there’s more that can be done.’”

This piece also appears in our May 2022 print edition.