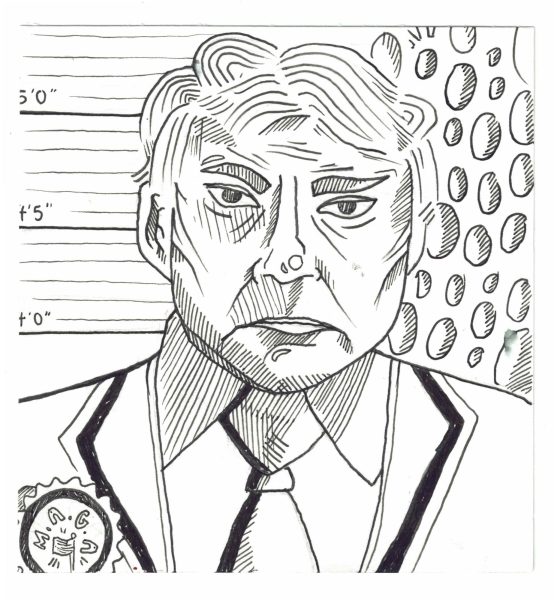

Putin’s Regime: Incompetent Beyond Repair

May 17, 2022

Tanks were left charred on the road, Russian troops fell for the same ambushes day after day, and their commanders were horrifically injured by their own soldiers in retaliation for nearly-suicidal attacks. Ever since the war between Russia and Ukraine began—or, more accurately, intensified—in late February, the Russian military has likened to a paper tiger: a terrifying yet weak entity, incapable of accomplishing its goals.

The West has finally realized what many analysts have always seen: the Russian state’s dysfunction. This goes beyond just the military. At every level, the security services, censorship apparatus, and even the most basic inner workings of Putin’s regime are plagued with corruption and incompetence.

Even the most basic inner workings of Putin’s regime are plagued with corruption and incompetence.

What about the terrifying attacks on Putin’s opposition? What about Sergei Skripal in Britain? Boris Nemtsov in Moscow? Alexsei Navalny in Tomsk? Don’t these incidents prove that Putin’s regime is both evil and competent? I’d argue the opposite. If anything, the fact that the world has an almost complete picture of the mostly unsuccessful assassination plots hatched by intelligence agencies such as the Federal Security Service (FSB), the Chief Intelligence Office (GRU), and the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) has proven that the modern Russian security services hardly fill the lethally competent shoes of their Soviet Union State Security Committee (KGB) predecessors. At their peak, the KGB and American Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) ensured that we would have no ledger of how many were slain during the Cold War. The Soviet KGB was usually either successful in their assassination plots, or able to cover them up if they failed. For instance, the KGB files of the Mitrokhin Archive released in 2014, described by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) as “the most complete and extensive intelligence ever received from any source,” detailed decades of successful KGB hits that were both successful and completely unknown to the public at the time.

How have modern Russian assassination attempts fared? Opposition leader Nemtsov’s murder was so infamous that it made him a martyr. The failed assassination of KGB agent-turned-MI6 informant Skripal was immediately exposed by British authorities, leading the Russian government to quickly fabricate an implausible story about the assassins being “tourists.”

Anti-corruption activist Navalny luckily survived his poorly-executed assassination attempt as well. In fact, Navalny later called his FSB assassin under the guise of a high-up security official, say- ing, “This is Ustinov Maxim Sergeevich, aide to Nikolay Platonovich Patrushev. I received your number from Vladimir Mikhailovich Bogdanov. I apologize for the early hour, but I urgently require 10 minutes of your time.” Navalny’s own assassin then immediately divulged his entire plot to poison Navalny, and why it failed so horrendously. The security services are a paper tiger.

The state failed to block a social media app.

What about Putin’s censorship apparatus? Russians don’t have free speech! While Russians are likely to be censored in open and public contexts, certain forms of communication are virtually free of censorship, though not by Putin’s choice.

For instance, the Russian government attempted to ban Telegram, a social media app often used by anti-Putin activists. The app was too well encrypted for Russia’s media censorship bureau, Roskomnadzor, to crack. In 2020, after two years of “banning” Telegram, Roskomnadzor announced that it “is dropping its demands to restrict access to Telegram messenger in agreement with Russia’s general prosecutor’s office.” The state failed to block a social media app.

And when crackdowns on internet freedom came during the Ukraine war, Putin failed to prevent access to other outside sources. His attempts led to a spike in VPN usage and anonymous online protest, bypassing the knockoff version of China’s “Great Firewall” that the government was trying to institute. The censorship apparatus is a paper tiger.

But what of Putin’s vast control over the Russian economy and state? Doesn’t Putin’s authoritarianism extend to Russia’s natural resources? Authoritarianism does not imply competence. The Putin regime’s unbridled corruption is rife with incompetence.

The modern Russian security services hardly fill the lethally competent shoes of their Soviet predecessor.

Russia’s greatest economic strength is its oil reserves, among the world’s largest. The regime is dependent on the exportation of oil; it is a key revenue stream for the government. So why hasn’t Russia, like countries such as Qatar, become wealthy from these natural resources? Corruption.

Anders Åslund’s book, Russia’s Crony Capitalism: The Path from Market Economy to Kleptocracy argues that “Putin is now trapped in a self-imposed system of kleptocracy—where he rules surrounded by a circle of friends from his Leningrad childhood, the FSB and private business partners.

The corruption inherent in Russia’s political system has also resulted in an enormous amount of offshore wealth. Nowhere, however, is this corruption more evident than in Russia’s vast energy sector.”

The Putin regime could easily use this oil wealth to form a social contract such as is done in the Gulf States, exchanging improved quality of life for increased state control. Instead, Putin elects to allow corruption to slide. The Russian economy is a paper tiger.

Putin is now trapped in a self-imposed kleptocracy.

This corruption doesn’t just end with natural resources. Russia’s military failures in Ukraine stem from deep corruption and incompetence at every level of the military. According to Politico , “systemic corruption in the country’s defense and security sectors” led to poor logistical performance and supplies, as money that was intended for both of these vital military services was put into commanders’ bank accounts instead of spare parts. The Russian state is a paper tiger.

The Russian regime remains a threat to democracy. However, Putin has sabotaged his own position consistently, and any more moves against other countries or his own people risk his reputation, safety, and Russia’s stability as a state. Putin often talks about how, when backed into a corner, a person will lash out at those attacking them like a rat. But this time Putin has no one to lash out at but himself, for the challenges he faces are his doing. Putin is a paper tiger.

This piece also appears in our April 2022 print edition.