Approaching Ten Years Since The Boston Marathon Bombings

May 17, 2022

“When you said you wanted to do the interview, I thought this would bring back a lot,” CRLS Assistant Principal Mr. Tynes remarked to the Register Forum. This April marks nine years since Dzhokhar ’11 and Tamerlan Tsarnaev ’05 murdered three and injured more than two hundred and sixty people at the 2013 Boston Marathon; we are now approaching the tenth anniversary.

History teacher Ms. Otty taught both Dzhokhar and Tamerlan. Otty told the Register Forum that “with every passing year, students know less and less about the Tsarnaevs. Many of them don’t know that they went to the school.” Still, many staff members at Rindge can remember the aftermath of the Boston Bombings intimately. After hearing the news, Tynes immediately called his brother, a paramedic. “He’s always covered the Marathon, stationed at the finish line … He said to me, ‘I’m OK. I can’t talk right now. It’s a mess, it’s horrible, but tell everyone I’m ok.’” Tynes recalled that his brother pronounced one of the runners dead. Simultaneously, Tynes was getting “phone calls from every major news station.”

The school was facing two unique challenges: “We had people accused of being the bombers here, and we also had people connected to our school who were victims,” Tynes said. A former teacher’s son and daughter-in-law lost limbs. In the days and weeks after the bombing, The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) came to CRLS, investigating students as potential suspects.

Principal Smith remembered the precautions the school had to take. “At graduation, I always say: When you leave, you’ll always be a Falcon. CRLS will always be your home. Cambridge will always be your community. Come back, and let us know about your new struggles and your new strengths. But in the days after [the bombings], we couldn’t let people come back into the community … We had to be careful. We weren’t able to let people just stroll back in.”

Eventually, once the FBI determined the Tsarnaev brothers were responsible, they stayed at Rindge to investigate their social and academic lives while in high school. About their social lives, a friend of the younger Tsarnaev, Zolan Kanno-Youngs ’11, said that “Dzokhar was the captain of the wrestling team. My little brother knew him as the guy that dropped me off at my place once. He had a lot of friends.” Smith expressed that the older brother “Tamerlan was here my first year. He didn’t have the ease of connection that his younger brother did. He tried very hard to connect.”

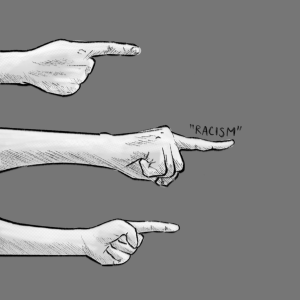

Academically, Ms. Otty explained her experience, saying, “[In 2015 I was] interviewed by the FBI a couple of times, and then was subpoenaed to be a witness at his trial, specifically because of the nature of what I teach in the class. That was scary. I feared criticisms of this liberal, progressive community that could suggest we might have done something to make them [the brothers] think this was ok.” Many of the on and off-record conversations I had about the Tsarnaevs grappled with this concept of ownership—the relationship between an individual and a community.

Smith asked: “What is a community? Is a community a destination people share? Is a community a shared set of values? Or is a community a place where people of different values and beliefs come together? At what point did they [the Tsarnaevs] not feel part of this community? Did they ever feel part of this community?” Otty added to Smith’s sentiment: “It’s human nature to attach oneself to the successes or the glory stories of the people we teach. I think of how little we know about the students in front of us. That’s not always a bad thing; I don’t need to know the inner workings of all my students. The Tsarnaevs were a clear reminder of how much trauma and hurt could be going on behind the scenes.”

Otty then mentioned Kanno-Youngs specifically saying, “one of Dzokhar’s close

friends is now a journalist for the New York Times, Zolan. But I’m not going to say that it was my class where Zolan cut his teeth on this or that. Just as I’m not going to say that, yes, my class was the class that did it for Dzokhar.” Kanno-Youngs believes Dzokhar’s experience at Rindge did not factor into his willingness to participate in the bombing. “There’s so much we don’t know about people I don’t think we should try to hide the fact that he went to Rindge I think it’s important that we talk about things that are uncomfortable to us.”

In 2016, 2019, and just recently, graffiti with extremist symbology was found throughout the building. Smith addressed these events saying that “On any given day, you will find the worst stuff in this community. Graffiti that’s meant to intimidate, marginalize, and scare. But on that same day, we had incredible acts of generosity and kindness. And that’s real-life.” When asked if the school should try to shelter students more, Smith answered, “I don’t think school should be a place where we insulate kids from the horrors of the outside world. I don’t think we can. Because, if what we’re doing here can only apply here—and not in the real world—then kids won’t be ready.”

Tynes expressed that despite Rindge’s many phases, some more painful than others, “You must always try to give kids the best of you and hope that’ll spark something.” Otty said that “the violence itself isn’t the important piece. What we should focus on is the way these events affected Cambridge, Cambridge kids.” Smith ended on a poignant and final note, paraphrasing Brian Steven’s Just Mercy, “We’re more than our worst day as a community. And we’re not as good as our best day.”

This problem also appears in our April 2022 print edition