The Early Decision Program’s Allure Rests on Misleading Data

December 25, 2021

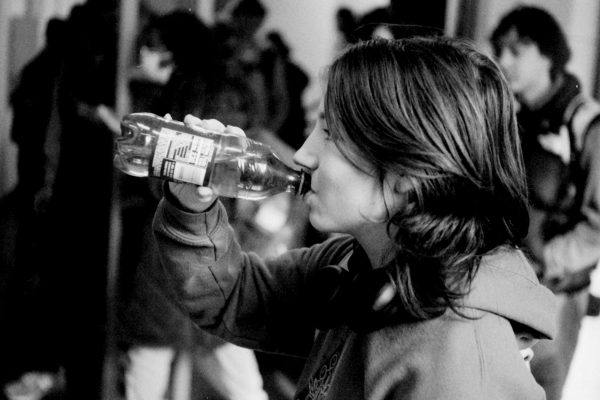

The tension in the weeks leading up to November 1st was practically palpable among CRLS seniors as they scrambled to visualize which historical figure they’d treat to a dinner and reflect on their Gluten Club leadership in the most profound way possible. The culprit was Early Decision: in exchange for a tighter deadline, one’s odds of admission to their top-choice college or university will, in theory, increase considerably. If accepted under the program, you are contractually obligated to attend.

With many elite universities dangling the prospect of better chances, many students feel compelled to try their luck in the early rounds. With the exception of the Ivy League’s “Big Three” (Harvard, Yale, and Princeton), which make use of a separate, non-binding Early Action program, almost every university in US News’ Top 30 offers a deadline for Early Decision (ED). To be fair, there is value in submitting this ultimate love letter (enter: demonstrated interest), but the hard numbers indicate that the advantages of applying ED are very falsely advertised. And, if anything, they benefit universities far more than any of their applicants.

Firstly, there are certain individuals whose spots in the incoming class are, informally, already secured. Athletes are a primary example: per their athletics website, over a quarter of Brown University’s 2021 early acceptees were recruited for a varsity sport. This pattern can be identified in the majority of elite schools, and yet, varsity athletes are still consistently factored into the released early admissions data.

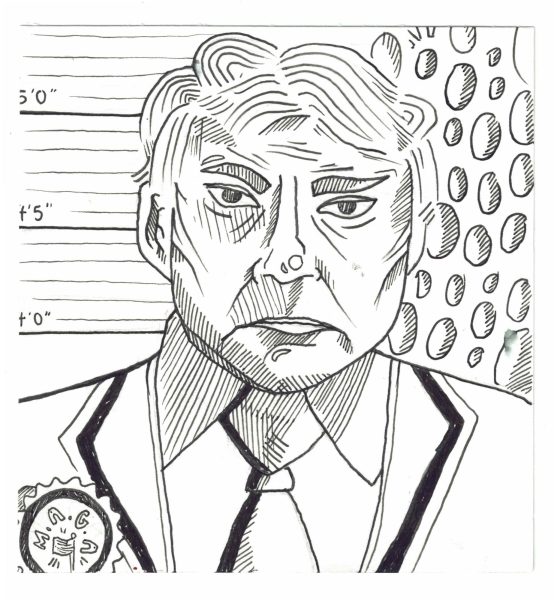

Many [colleges] intentionally advertise to students that they know they’ll reject, simply because it drives the acceptance rate down.

Legacies stand to profit off of ED as well, maximizing their inherited leg-up on most of the applicant pool (which is especially relevant to established Ivy or Ivy-adjacent “dream schools”). Some aren’t given a choice; for instance, UPenn and Cornell will only consider your coveted familial status if it’s on their desk in November, instead of the following winter when regular applications arrive. These groups, in combination with the much higher concentration of competitive hopefuls flooding the first wave of applications, account for most of the percentage bump.

In that case, why does Early Decision exist in the first place? What many tend to forget is that colleges are businesses, and that money and numbers are very powerful. A higher participation in their Early Decision program enhances two crucial data points: a lower acceptance rate and higher yield rate.

Yield rate is the most important statistic when it comes to determining college rankings. It’s the percentage of accepted applicants that go on to attend, and it dictates how desired a spot at the university is (Harvard and Stanford are tied nationally for the highest at 82%, according to US News). The legally-binding, full-commitment Early Decision program artificially bolsters yield rates, and the greater number of qualified applicants they can accept through ED, the better.

But there are quantitative benefits to attracting unqualified applicants, too. Many institutions flag down and intentionally advertise to students that they know they’ll reject simply because it drives the acceptance rate down. Tulane University is an often-referenced example; in 2019, their admissions office purchased a staggering 300,000 email addresses from the College Board to peddle to (per Tulane’s student newspaper). Their outreach was strategic in seeming personalized, with snippets like “priority consideration” and “automatic fee waiver” intended to encourage recipients to apply. These words were empty words; Tulane’s acceptance rate has dropped from 26% to 13% in only three years.

In short, the Early Decision program exists to serve the institution, not the student. Sorry to disappoint—your chances of acceptance are, roughly, the same as they would be otherwise.