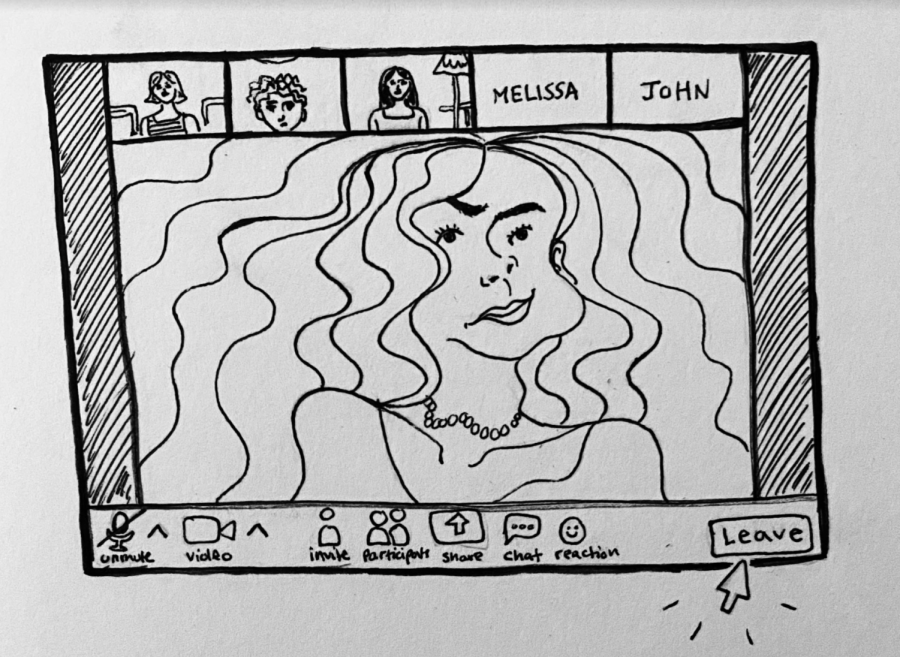

Zoom Dysmorphia: The Reality of Video Conferencing

October 2, 2021

Staring at your reflection nowadays has become unavoidable. However, looking at yourself on a screen daily, for hours on end, has led to more detrimental effects than ever imagined. With the increased use of video conferencing tools—such as Zoom and Google Meet—during the COVID-19 pandemic, facial dysmorphia, the unconscious distortion of one’s appearance and facial features, has become more prominent.

This mental health condition did not originate during the pandemic, although recently, the obsession with appearance on video calls has led researchers at Harvard University to study the effects of their coined term, “Zoom dysmorphia.” This phenomenon affects Zoom users on a physical and psychological level, and people are now desperately wishing for a change in their appearance. Unlike “Snapchat dysmorphia,” the conscious distortion of the face because of unrealistic filters, Zoom dysmorphia is the less obvious distortion caused by the warped camera lens, contributing greatly to people’s self-awareness. According to the New York Post, Dr. Shadi Kourosh, who conducted the Harvard study, explained, “The lens is akin to a ‘funhouse mirror’ warping noses to look bigger, eyes smaller and showing the whole face at a closer angle than most people would ever see it.”

… Zoom dysmorphia is the less obvious distortion caused by the warped camera lens, contributing greatly to people’s self-awareness.

The consequences of the distortion have led to an abnormal prioritization of appearances. Cosmetic plastic surgeries increased all over the world, including a 70% increase in consultations in Britain this March, The Guardian reported.

In addition to plastic surgeries, Zoom dysmorphia has brought on a wave of anxiety and stress, especially revolving around the return to in-person activities. In Kourosh’s study, 70% of over 7,000 surveyed individuals felt stress or anxiety regarding appearance with the return to in-person interactions. A CRLS student, junior Annie Ramsdell, empathizes with this stress. “Going back in person and seeing everyone after so long was pretty scary and stressful because I just felt myself subconsciously comparing myself to other people and how much they changed over quarantine versus me.” She continues, “When we were on Zoom, we had a choice to have our cameras on or off… Whereas now at school, if you’re feeling self conscious you still have to show up and you don’t have that choice. That can be pretty nerve-racking.”

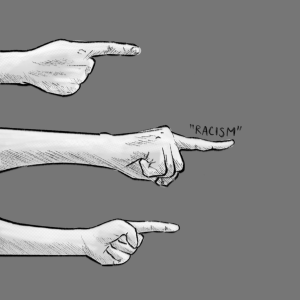

Being stuck at home meant people were constantly on their phones, primarily on social media, whenever they weren’t on video calls. The existing and lasting self-scrutiny stemming from social media usage exacerbated people’s self-awareness, as well as their comparisons of themselves with others, only worsening with the use of video conferencing.

Returning to in-person learning, the long-term effects of Zoom dysmorphia are still unknown. However, in order to discover these impacts by making these discussions less taboo, bringing awareness to this topic and other related issues will help. Isabel Wigginton ’23 told the Register Forum, “I wasn’t aware that the camera was morphing my face… We definitely need to start talking about this psychological issue with its effect on mental health.”

This piece also appears in our September 2021 print edition.