The Tyranny of the Grand Old Party

December 22, 2020

The Republican Party has won the popular vote only once in the last eight presidential elections. Yet even still, two of the five most recent presidents have been Republicans, and they have appointed six of the nine sitting Supreme Court justices. Both Republican presidents we have had in the 21st century ascended to the Oval Office despite losing the popular vote to a Democrat. Many of the Republican Party’s current positions are unpopular—two thirds of voters support a $15 minimum wage, higher taxes on the wealthy, and legalizing marijuana. In fact, the GOP position on preexisting conditions is so unpopular that voters literally do not believe that any politician could possibly hold said views.

So how exactly have Republicans remained in power despite a lack of support from voters and highly unpopular positions? Our broken electoral system. It starts with the Electoral College, which gives disproportionate weight to rural white voters who tend to favor the GOP. As I’m sure readers are aware, Donald Trump won the presidency in 2016 despite receiving nearly three million fewer votes than Hillary Clinton. This November, Joe Biden won seven million more votes than Trump, yet only carried the tipping point state of Wisconsin by 20,000 votes (0.6 points). In fact, Biden won none of the swing states he carried by more than three points, despite a four-and-a-half point national lead. In other words, the swing states were to the right of the country as a whole, largely because they are whiter than America as a whole (remember, white voters tend to break for the GOP). A recent study by the University of Texas found that Republicans should be expected to win 65% of presidential elections in which they narrowly lose the popular vote.

But no other institution is as biased towards rural whites—and by extension the GOP— than the Senate. According to calculations by David Leonhardt of the New York Times, the Senate gives the average black voter only 75% of the representation it gives the average white voter. For Asian voters, it’s 72%; for Hispanics, only 55%.

The median state is 6.6 points more Republican than the nation as a whole, meaning that anything short of a modern-day landslide prevents Democrats from winning a Senate majority. Because Senate confirmation is required for cabinet and judicial appointments, this Republican skew precludes a Democratic president (i.e., Joe Biden) from doing the bare minimum of governing unless they win the landslide needed to avoid partisan gridlock. Even if the Republicans win both Georgia runoffs, Democratic senators will represent 20.3 million more people; if Democrats win both seats the chamber will be split 50-50, with the Democratic half representing 41.5 million more people. A system in which one party consistently remains in power despite representing a minority of voters is not a democracy.

Not satisfied with the titled playing field, Republicans have chosen to make it harder to even cast a ballot. The states, often called the “laboratories of democracy,” have been turned into petri dishes of voter suppression and gerrymandering. In 2010, the GOP won unified control of North Carolina. Under the leadership of then–State House Speaker Thom Tillis, they passed a strict voter ID law and drastically cut early voting hours, both of which disproportionately hurt nonwhite voters. The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals found that these laws “targeted African Americans with almost surgical precision.” In 2013, the Supreme Court voted along party lines to gut the 1965 Voting Rights Act (VRA) in Shelby County v. Holder, with Chief Justice Roberts’ majority opinion stating that the law was written to combat racial discrimination in the past that “no longer” exists today.

Sure it doesn’t, John. In 2017, under Georgia’s “exact match” law (banned under the VRA prior to Shelby), then–Secretary of State Brian Kemp removed 670,000 voters from the rolls—80% of whom were nonwhite (and therefore more likely to vote for Democrats). In 2018, Florida voters passed Amendment 4—intended to overturn a Jim Crow–era law denying felons who served their time the right to vote—by an overwhelming margin.

The law would have restored the franchise to 1.4 million people. Florida Republicans quickly passed SB 7066—a law that requires ex-felons to repay all fines they incurred during their trials, even though the state of Florida itself often does not know and refuses to find out the total amount an ex-felon owes—in effect making voting pay-to-play. Combined, voter ID laws and voter purges have removed at least 17 million people from voter rolls nationwide, with purges surging after Shelby in jurisdictions previously covered by the VRA.

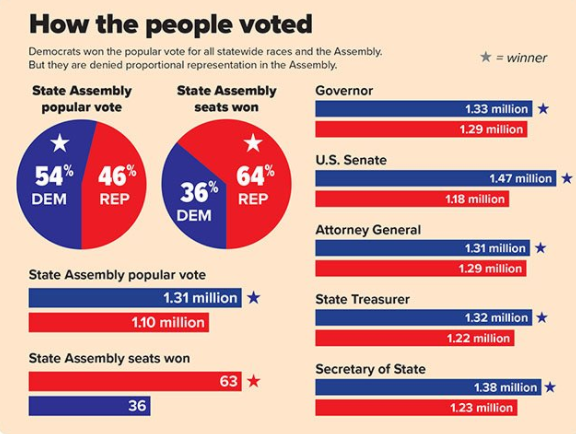

Even if you manage to cast a ballot, the GOP has tried to ensure that it won’t matter. Due to gerrymandering—politicians redrawing legislative districts for partisan advantage—after the 2010 Census, Republicans also have an edge in House races; in 2012 they maintained their House majority despite winning 1.4 million fewer votes than the Democrats. According to data from the Cook Political Report, the median House district is three points more Republican than the nation as a whole, despite America leaning slightly Democratic in general. In Wisconsin, Republican gerrymandering has been so extreme that it is no longer accurate to say that the state is a democracy.

In 2018, 54% of Wisconsin voters chose a Democratic candidate for the state Assembly, yet Republicans carried 63 out of 99 Assembly seats. Even when in the minority, the GOP manages to subvert democracy: Oregon Republicans literally fled the state to deny a duly elected Democratic supermajority the quorum needed to pass a cap-and-trade bill.

Republican politicians have faced very few consequences for their anti-democratic actions. Brian Kemp is now the governor of Georgia, Thom Tillis was just reelected to the Senate, and Mitch McConnell has allowed H.R. 4—a bill passed by the House to nullify the Shelby decision and restore the 1965 Voting Rights Act—to sit on his desk gathering dust for over a year now. Republicans and Democrats have long disagreed on a litany of issues, but both parties once shared a commitment to democracy. Sadly, that is no longer true.