Changing the Male Narrative: It’s OK for Boys to Cry

November 29, 2017

Feminists often make “us versus them” statements, portraying men as the enemy and women as the victims. The truth is that feminists of all kinds, whether mothers, peers, sisters, or coaches, have a huge opportunity to create change in the everyday life of a young boy. From the minute a boy is born, he is bombarded with ideals of what it means to be a man, what the ideal boy is like, how he behaves. Boys are often taught to hide their feelings not only by their mothers and fathers, but also by their peers. Encouraging boys to bottle up their emotions and hardships seems to cause them to resort to violence more often than girls and women. Of arrests, 73% are on males. Allowing boys to express themselves could change that statistic.

Studies have shown that boys younger than five tend to emote more and are more socially aware than girls of the same age, but by age fourteen the statistics have changed drastically. Boys are taught to turn their sadness and fear into anger, limiting their emotional outlets. This pattern begins with outdated societal ideals, but also in a much simpler place—the toy aisle. Oddly enough, the partitioning of toys by gender only began to appear in the 1980s and 1990s. Different toys teach different skills. Dolls can teach kids how to take care of another person and to feel empathy. Trucks and legos can teach spatial awareness and motor skills. Consequently, gender-specific toys leave one gender with an entirely different set of knowledge than the other. This affects us, if only subconsciously, for the rest of our lives.

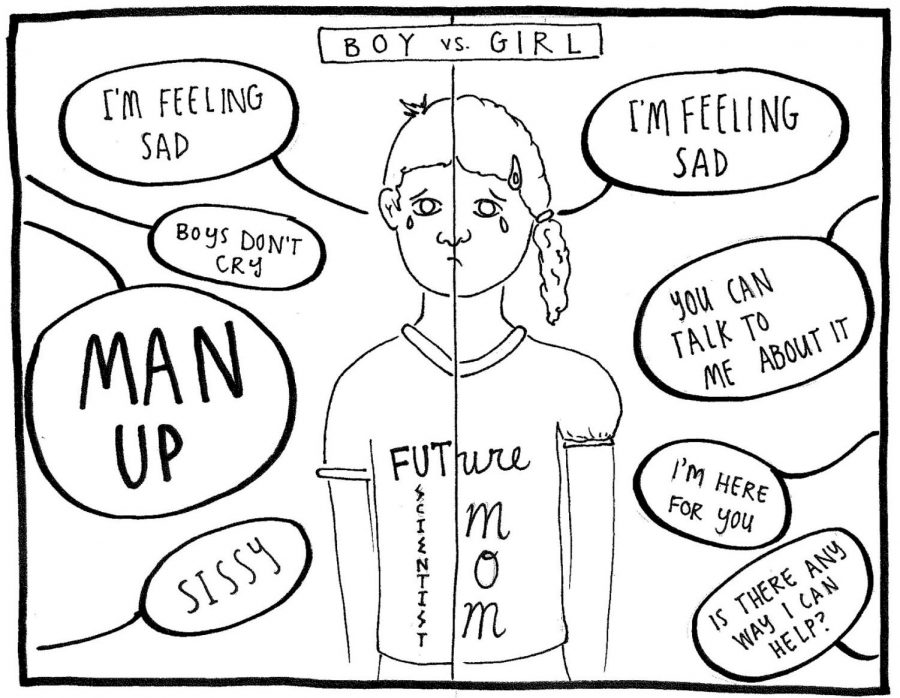

Boys (and girls) are taught from an extremely young age that girls are inferior. At home, on the playground, and on the field, boys are peppered with phrases like “don’t throw like a girl,” “don’t cry like a girl,” and “be a man.” By telling boys that girls are weaker—and overall lesser—than them, we ingrain in boys a sense of entitlement which they deserve no more than girls.

Masculinity is hard to define. Today, society often defines a “real man” with adjectives like “strong,” “powerful,” and “courageous.” To be a man is to be removed from anything considered remotely feminine. It isn’t enough for a person to say he is a man; throughout his life he must constantly prove his masculinity just to earn his gender label. By being told that crying and expressing emotions other than anger is a sign of weakness, boys aren’t given a big enough “emotional toolbox.”

By confining boys to such a small box of what is acceptable, we create a society of men who are shamed for showing who they truly are and who must struggle with their identity throughout their entire lives. A study done by the mental health organization CALM found that 42% of men felt they needed to be emotionally strong in a crisis while only 17% of women felt the same way. Girls are also much more likely to turn to a friend and talk about what they are going through than a boy. This pattern leads to boys hiding their feelings and even serious conditions such as depression. According to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, the suicide rate among men is three and a half times higher than for women.

To fix this problem we must start at the beginning, whether in the toy aisle when shopping for children or on the playground when a boy falls down. By high school, we can already see the differences between many boys and girls—the way we talk to each other, the way we say hello in the hallways, what we do when we feel down, stuck, or frustrated. Of course there are boys (and girls) who don’t fall within this stereotype, but they are constantly being othered, separated, and told they are different or somehow inferior to those who embody the “ideals” of being a woman or man. We need to change those ideals. Boys should be taught from a young age that it is OK to cry and to feel helpless at times, and society needs to start accepting boys with healthy emotional expression.

This piece also appears in our November print edition.