Combatting a Stubborn Culture

An In-Depth Look at Sexual Harassment and Violence at CRLS

December 21, 2018

When a current senior was taking the MCAS in her sophomore year, another student sitting behind her began whispering sexual comments to her. The student told her Community Meeting (CM) teacher that she “couldn’t be in the room with him because he was trying to touch [her], he was whispering in [her] ear, [and] it was really uncomfortable.” She took the rest of the MCAS in her Learning Community (LC) office, filed an incident report, and, eventually, the student who had harassed her was moved to a different CM.

The CRLS Intersectional Feminism Club, also known as “Fem Club” or “Club 1,” was concerned about exactly this kind of incident when they held a walkout in April of 2016, a year before this student was harassed. Their walkout was intended to urge the school administration to change its response to sexual harassment and sexual violence, as well as the culture that creates these behaviors.

The club, along with other CRLS students, wrote to the administration with thirteen demands, which included more training for teachers, making information about the reporting process more accessible, and hiring a Title IX officer. Title IX is a federal law that prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in federally-funded education programs, and Title IX officers are responsible for investigations into allegations of Title IX violations.

Pictured: Fem Club meeting.

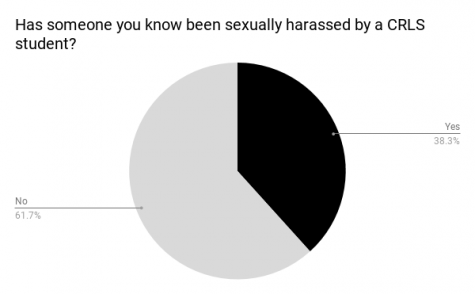

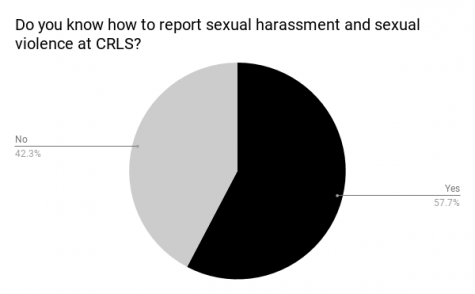

In the two years and eight months since these students wrote the letter, CRLS has made several significant changes, including modifying the policies around how sexual misconduct is reported and raising more awareness about the process itself. The district also hired a new Title IX officer in 2017. Still, according to a recent survey of 200 students conducted by the Register Forum, a significant number of students are still experiencing sexual harassment and sexual violence, indicating that more progress needs to be made.

Sexual Harassment and Sexual Violence at CRLS

The Cambridge Public Schools Non-Discriminatory Policy and Prohibition Against Sexual Harassment defines sexual harassment as “unwelcome sexual advances, whether they involve physical touching or not,” and defines sexual violence as including “rape, sexual assault, sexual battery, sexual abuse, and sexual coercion.”

38% of the 200 students who took an RF survey said that they knew someone at the school who had been sexually harassed by another CRLS student. Nearly a quarter of students said they knew a CRLS student who had experienced sexual violence by another CRLS student. Only 16% of female students said they felt “very safe” from sexual harassment and sexual violence at CRLS. In contrast, more than half of male students said they felt “very safe” from sexual harassment and sexual violence on campus.

Senior Gilli Danenberg told the RF, “I feel like every other girl I’m talking to is like, ‘I’ve been harassed.’” Danenberg also recounted an experience she’d had with another CRLS student. “The guy was pushing for it and I said ‘no,’” she said. “And then he kept pushing for it, and I said ‘no.’ I eventually had to say ‘no’ so many times where I was like, ‘This is absurd.’”

According to senior Annie Slate, the President of Fem Club, the biggest contributor to the harassment Danenberg and many others say they have experienced is the school’s culture. “There’s a culture of objectifying women, disrespecting what they want to do with their bodies [and] the decisions that they make,” she said. “I think there is also a culture of thinking that there aren’t consequences for those actions.”

Junior Eli Siegel-Bernstein agrees with Slate. “I think that there’s a lot of misogyny that’s ingrained into the culture at CRLS.” He said that these attitudes can be hard to recognize since CRLS is regarded as one of the most liberal schools in the country.

While many students feel the school could be doing more, the CRLS administration has been working to create a school culture that does not tolerate sexual harassment and sexual violence. “The climate that has to be set is, when you see folks in the hallways saying and/or doing things, you can’t ignore it. You have to notice it, you have to call it out … and then you have to make a report,” said Principal Damon Smith. Mr. Smith held a training for staff at the beginning of the year centered around an attitude called “notice, interact/intervene, and report,” which “sets the dynamic up that we don’t accept” certain kinds of behavior.

Policies and Procedures

Unlike the procedures at the time of Fem Club’s letter, students can now report sexual harassment and sexual violence to any adult in the school, not just their dean, and can have a friend or another person in the room with them. The administration has also tried to make the reporting process more visible through posters in bathrooms and, most recently, through two X-Blocks, one which focused on reporting in general and the most recent one on respect and sexual harassment.

Nevertheless, 42% of surveyed students said they did not know how to report sexual harassment and sexual violence at CRLS. In fact, freshman Stella Astbury said, “I didn’t even know there [were] policies about it.” Senior Bella Lima said that “it’s not a thing that’s really talked about often.”

Ramon DeJesus, the Director of Diversity Development and the Title IX officer for the district, acknowledges that some of the policies and resources regarding sexual harassment and sexual violence are unclear to students.

The school and district are trying to address that, in part by attempting to make DeJesus more accessible to students. “I want to be more known to students as a resource, period … for these types of concerns [and] for anything else,” he says.

When the CRLS administration is alerted by a faculty member or student of an allegation of sexual harassment or violence, they are required to tell the student’s parents or guardians if that student is under 18. Then, if the allegation is not a criminal offense (rape and assault are examples of criminal offenses), the school investigates the claim, talking to witnesses and the accused to make a judgement as to whether the allegation is substantiated. Next, they determine the appropriate consequences, which range from having a conversation with a student, to suspension, to expulsion.

All adults at CRLS are “mandated reporters,” which means that they are legally bound by state law to report to the Department of Children and Families if they suspect that a student is being abused or neglected. As LC L Dean of Students Susie VanBlaricum says, “There is a reason we’re mandated reporters. It’s because students aren’t old enough to handle these big things alone.”

A student, who wished to remain anonymous, told the Register Forum that he was sexually harassed by another CRLS student in front of a faculty member. The student did not feel comfortable reporting the incident, and the faculty member did not report the incident either. “It’s really unacceptable that that teacher never reported it,” said the student.

However, Slate says that “the nature of mandated reporters means that there is no place to just talk about what’s happened to you,” if you don’t necessarily want to report the incident.

Many members of the CRLS community that the RF interviewed noted that students can be reluctant to speak up about these incidents.

According to Slate, this is often due to a fear that, when someone reports an incident, “they are going to lose control over what happens.” Slate noted that many people who do report incidents feel like they are not kept up to date through the investigation process.

Pictured: CPSD Director of Diversity Development and Title IX Officer.

Mr. DeJesus suggested another reason students stay quiet: “The folk who are subjected to those things—like sexual harassment, like discrimination—don’t feel like they have [enough of] a voice to say, ‘Hey, this happened to me, believe me.’” The solution, he said, is to both help students find the courage to uncover that voice, and for the administration to have “the courage to do something about it when we find that a wrong has been committed.”

Slate would like there to be an adult—maybe a social worker—who is not a mandated reporter that students could simply talk to about any experiences with sexual harassment and sexual violence. She says that Fem Club has tried to be a space where students can come to talk about their experiences, but that it can’t be the only space, since “high schoolers are not usually equipped to deal with each other’s trauma.”

Health Education

Health teachers in Cambridge teach about sexual harassment and sexual violence in their classes. At CRLS, the health teachers use Planned Parenthood’s curriculum Get Real as a foundation, and supplement it with materials they find on their own and with another curriculum called Safe Dates, which is about preventing dating abuse. Dating abuse is a pattern of abusive behaviors used to control or exert power over a dating partner.

However, many students at CRLS feel as though the health education they have received hasn’t gone into enough detail about sexual harassment and sexual violence. “Sexual violence and consent was never included in the health curriculum,” said Siegel-Bernstein. “There’s no education about which behaviors are acceptable and which behaviors are not acceptable.”

Less than half of students said on the Register Forum’s survey said that they had learned about topics such as the characteristics of healthy and unhealthy relationships, the definition of sexual consent, factors like drugs and alcohol that impair a person’s ability to give and receive sexual consent, situations and behaviors that constitute sexual harassment and sexual violence, and what to do if you or a person you know experience or witness sexual harassment and sexual violence.

However, health teachers Patrick Kantlehner and Nicole Read are both new this year and are working together to modernize and expand the existing curriculum, including the topics mentioned above.

In addition, a group of students, led by Slate and Sisters on the Runway president Robie Scola ’19, are teaching about consent in freshman health classes this year, something that Scola and Slate feel was lacking in their freshman own health classes.

Slate says, “There was no discussion as to when do I say, ‘Hey, can I do this?’ There was no discussion of consent.”

Necessary Change

One important change students feel the school could make to reduce the prevalence of sexual harassment and sexual violence is to enforce harsher consequences for students who have harassed or assaulted other students.

“People are not willing to report [incidents of sexual harassment and sexual violence] because they think that nothing is going to be done,” said senior Marly Ciccolo. “If [the administration] really wants that culture to be put to the side and destroyed, they really need to start doing something and taking action.”

Of the students who said that they had been sexually harassed by a CRLS student, none of them said that they had reported the incident. Similarly, none of the students who said they had experienced sexual violence by another CRLS student said that they had reported it.

Lima elaborated on why students tend not to report: “It takes a lot of strength to go and tell someone about something you’ve experienced like this. When it’s not dealt with in the correct way, or the way you know it is supposed to be dealt with, it kind of discourages you.”

Other CRLS students noted that it can be hard to report quick incidents of sexual harassment that happen in the hallway, as the victims might not know the perpetrator’s name or even what they look like.

Mr. Smith acknowledges that reporting is only part of the answer. “The reporting process is good, but it’s … not the solution. The solution is developing a community, curriculum, [and] experiences where we don’t have to have a reporting process because everyone knows what’s appropriate behavior, [and] what’s not appropriate behavior, and how to address that, or how to respond and behave that way.”

Last year, Mr. Smith said he tried to make Wellness 2 mandatory as a way to develop that kind of community. “We are hoping to get more students into Wellness 2 because from what we’ve understood, Wellness [1] at ninth grade is good, but as students get older they need more opportunities to walk through it,” he explained.

And while it may seem like preventing sexual harassment and sexual violence from happening in the first place is an insurmountable task for one school to take on, Alan Berkowitz, a national expert in helping schools and communities come up with ways to address sexual violence who was recently quoted in an NPR article, told the Register Forum in an email, “As with ecological or green issues, change starts at home with oneself and expands. Not feeling that you can change everything does not justify not changing something.”

For junior Kayden Conelly, it is clear what needs to be changed. “I want people to actually get resources,” he says. “I want people to actually be believed. I don’t want people to be like, ‘I can’t come out and and say anything.’ I feel like that’s what needs to happen.”

History teacher Kevin Dua thinks that strengthening resources and the reporting process are important, but that in order to eradicate the culture of sexual harassment and sexual violence, there needs to be a complete change in the way students think about sexuality, gender, and power dynamics.

In essence, “there has to be a revolution,” Mr. Dua said, “with all hands on deck.”

This piece also appears in our December 2018 print edition.