Diversity in Cambridge: Part 2

A History of High School Education in Cambridge

May 30, 2018

In 1636, Elijah Corlett created the first school in Cambridge: the Latin School. The school was well-known both because of Corlett’s leadership and because of its proximity to Harvard University. In fact, Harvard University’s president at the time, Henry Dunster, paid for the building of the school. The Latin School served only boys and focused on preparing students for Harvard. In 1642, the first school committee in Cambridge was elected, and as the areas that made up Cambridge began to expand, more schools were built.

Today, Cambridge Rindge and Latin is one of 18 schools within the Cambridge Public School District. CRLS alone serves nearly 2,000 students of the 7,000 within the district. It’s recognized as one of the top public high schools—in one of the top school districts—in the state, as well as in the country. So how did the Latin School, a one-room schoolhouse for boys in the heart of Harvard Square, transform into the sprawling, diverse, and nationally recognized school that it is now?

The Origins of CRLS

Before the 20th century, there were several different high schools scattered throughout Cambridge that each served a different community in the city. There was the Auburn Female High School, the Otis School for East Cantabrigians, the Hopkins Classical School which aimed to send students to Harvard, the Rindge Technical School for vocational training, and the Howard Industrial School, which trained African Americans for domestic service.

In 1912, the Cambridge English High School and the Cambridge Latin School, along with other high schools in Cambridge, merged to form Cambridge High and Latin. After this merger, there were two main high schools in Cambridge: Cambridge High and Latin and Rindge Technical School.

“The predominant [number of] black males went to Rindge Tech, ’cause it was like, ‘you’re not going to college, you’re black, you should go to Rindge Tech and learn a trade.’ So only a handful of black guys went to Cambridge High and Latin, and they all knew each other, and they’re all so proud that they went to the college-bound school,” Ms. Banks, CPSD’s conflict mediator and a former CRLS student, told the Register Forum.

In 1977, Cambridge High and Latin and the Rindge Technical School merged to form Cambridge Rindge and Latin.

Leona Martin, who was born and raised in Cambridge, graduated from Cambridge High in 1971. She looks back on her time as a student fondly, saying, “For the most part, we all got along. I really enjoyed that, and I always brag about that, especially when I have a lot of friends who aren’t from this area who didn’t experience what we did. They may have gone to segregated schools, and they just didn’t have the kind of diversity and the mix that we had.”

Mr. Silva, director of safety and security at CRLS, graduated from Rindge Tech in 1969. He remembered tension between students at both of the high schools: “There was a lot of racial unrest. We actually saw racial riots up here … I remember looking out the window and seeing the riot police with shields, with helmets on, with those big night sticks. I remember seeing tear gas canisters bouncing out there,” said Mr. Silva. He continued, saying, “I remember Rindge, kids looking out the window, black kids and white kids, and just not getting involved in that … but there were people who did go out who wanted to get involved.” Mr. Silva concluded, adding, “I’m not going to blame the Latin crowd,” but that he saw more people from Cambridge High and Latin School than Rindge Tech involved in the riots.

Mr. Ellcock, a safety specialist at CRLS who graduated from Rindge Tech in 1969, said that while these tensions existed, inside the school “was neutral territory.” Both Mr. Ellcock and Mr. Silva affirmed that students of all backgrounds were still friends with each other during this period. In particular, Mr. Silva remembered getting to meet people who were different from him when he played sports. “The good thing for me about playing sports in middle school time … was that I got to play in different parts of the city. So, like, when we’d go to the part of the city that was called The Coast, it was predominantly a black neighborhood … so I started to meet people from other races and different backgrounds.”

Transitional Strife

With the two largest high schools in Cambridge combining to create a student body well over 2,000 students in 1977, there was bound to be transitional strife. Combining the vocational, blue-collar, all-boys school of Rindge Tech and the college-preparatory, co-ed school of Cambridge High was no easy task.

Ms. Banks, who graduated from CRLS in 1986, reflected, “Racial tensions started rising. We were in the Civil Rights Movement just like everybody else, we were in the Black Power Movement just like everybody else, so there were racial tensions.”

In 1980, Anthony Colosimo, a white student from East Cambridge, was murdered in a fight at CRLS that officials at the time said had “racial overtones.” Mr. Prince, dean of students for Learning Community S and member of the CRLS Class of 1988, told the Register Forum that the incident “was emblematic of the relationships” between students of different races in the city.

Proposition 2.5

In the early 1980s, in addition to the tumult at Rindge, the state was also undergoing massive economic changes. Proposition 2.5, a property tax reduction, was passed in November of 1980 in Massachusetts. The property tax reduction came with a large cost to public schools. Because of the challenges that came from the recent merging of the two schools, the city originally tried to direct most of the budget hits towards the elementary schools. However, by 1982, the district had to cut its budget by 15%, and the effects reached CRLS.

The budget cut led to mass firings. School Committee member Fred Fantini, who was first elected to the Committee in 1983, remembered his early days dealing with the effects of the budget cuts, saying they had to lay off “a few hundred teachers at the time.”

While laying off teachers, the district made purposeful choices in order to maintain the diversity of the school system. “One of the things I was able to accomplish, actually, with [current School Committee member and former guidance counselor] Laurance Kimbrough’s father was … the attack not to lay off any teachers of color at a time when all unions were based off seniority.” The School Committee at the time, against the wishes of the teacher unions, defined the prioritization of retaining teachers using three categories: experience in a subject, commitment to a particular program, and race.

The House System

The divisions that existed within CRLS, though, were cemented into its structure. From its formation in 1977, CRLS used a house system to organize students. For nearly 25 years, there were six different schools—Pilot, Fundamental, A, B, C, and D—housed within one building.

The Pilot School was an alternative educational environment, where teachers were called by their first names and students had more authority over their learning. It was a popular choice for Cambridge students. School Committee member Laurance Kimbrough, a lifelong Cambridge resident, remembers the attraction that many famous Cambridge residents—especially those of color—had to the Pilot School, commenting, “What I remember about the Pilot School as a kid … was the strength of the upper-class, middle-class, families of color being very prominent in the school. Just to give some historical context, you had Bob Moses, civil rights activist—his kids were in Pilot. You had Charles Ogletree, renowned professor at Harvard Law School—his kids were in Pilot.”

Another school within CRLS was the Fundamental School, which was a strict, heavily disciplined school focused on the basic elements of education: math, writing, and reading. As Gavin Kleespies, director of programs at the Massachusetts Historical Society, told the Register Forum, the Fundamental School was like a “Catholic school without God.”

With regards to the makeup of the rest of the houses, A house was predominantly white, upper-middle class, college-bound students; B house was predominantly black students and lower-middle class white students; C house was a conglomeration of students; and D house was mostly international English language learners. Students chose their houses, though students who wanted to go to the Pilot School had to apply.

“When you met a kid or knew a kid from a certain house, you kind of developed an understanding of that kid—his or her background. You had an initial impression. Sometimes you were wrong, but most of the time you had a fixed mindset,” noted Mr. Prince.

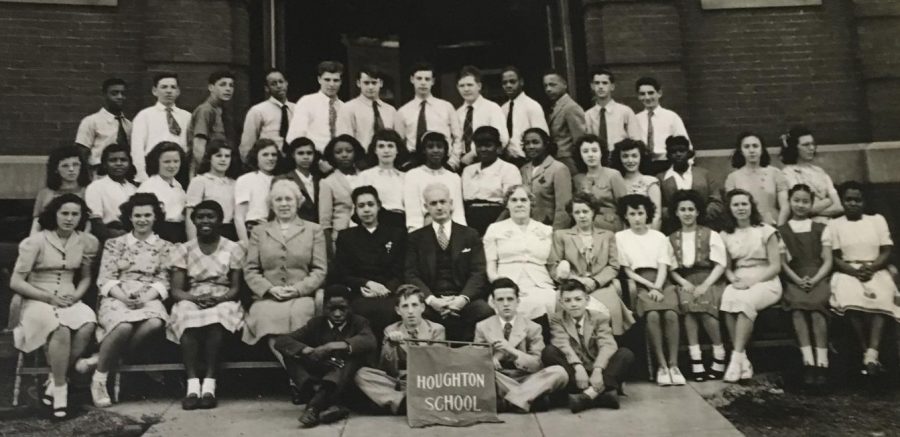

Pictured: The Cambridge Manual Training School in 1938, which later became Rindge Tech.

The Struggle for Equity

Kimbrough was a freshman at CRLS in 1994. His brother had attended Pilot before him, but Kimbrough said that his brother’s experience was much different than his own, pointing to the end of rent control in 1994 as a factor: “I think my experience at Pilot was different than my brother and his friends who were there almost six years earlier, in that there just weren’t as many middle-income [and] upper-income African American [or] Latino families just in the school at that point [after rent control].”

By the end of the 90s, the house system was under scrutiny from certain students, parents, and staff. Fantini recounted why the district made the decision to end the house program, saying, “[Pilot] was a high-achieving school. They still have their reunions every year. There were a lot of great things about it. But what it wasn’t was a diverse environment. It wasn’t diverse at all. Kids of color weren’t really benefiting from that experience.” Fantini said the Committee hoped to raise the standards of all the programs, rather than just one, and they saw removing the house system as the best way to do that.

Martin’s daughter attended CRLS in the early 90s. Martin compared the school when she was there to when her daughter was, saying, “I think the difference that I would say when she was there is that they were, oh gosh, those kids were kind of wild. I don’t think they were as serious about their education as we were … I found that a lot of the kids that she hung out with, they weren’t as into school as we were.”

In 2000, the house system was abolished in a plan approved by the School Committee as increasing numbers of community members felt as though the system was inequitable. Kimbrough, who graduated just before the end of the house system, commented, “I certainly know that I benefited from being in Pilot, but I was OK when it went away, because I knew that I was getting a different educational experience than the people in the [rest of the] school, and that just wasn’t right.”

While some students and parents were ready to see the houses go, others were not. In particular, some students feared that without the house system, they would not be able to develop strong identities. Emily Gregory, a Pilot student who graduated in 1996, told the Harvard Crimson in 2000, “Restructuring will lose the culture that CRLS teachers have worked hard to create. What we liked about our school was how different it was.”

In addition to eliminating the house structure, in the early 2000s, CRLS also experimented with deleveled classrooms for 9th and 10th grade students. Again, the goal was to achieve as much equity in the school as possible. Parents, teachers, and students—as well as other community members—believed in the benefits of heterogeneous classes, feeling as though eliminating tracking was the only way to make classes truly equitable and ensure that students got to experience the school’s diversity on a day-to-day basis.

However, in practice, it was difficult for the school to make heterogeneous classes work. According to a Boston Globe Magazine article from 2003, both high-achieving students and low-achieving students didn’t do as well as they had before, some teachers felt as though their classes were chaotic and disorganized, and some teachers had trouble teaching students of so many different abilities in one class.

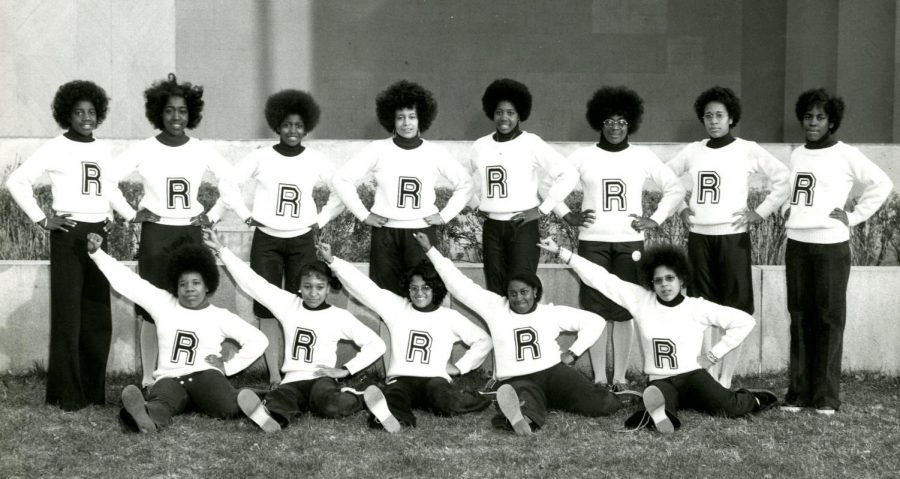

Pictured: Cheerleaders for a Rindge Tech sports team in 1973, four years before the high schools merged.

These drastic changes at the beginning of the new century had significant impacts on the school. Fantini appreciated the hard work then-Principal Paula Evans put into the district to make these changes, and noted that many of the initiatives she pushed are being put into place today, like the Level Up initiative the district began to implement this year. The problem, he said, was the timing of her initiatives. Every five years, the high school is evaluated by national officials. The timing of Evans’s massive changes fell just as these evaluators came to Cambridge. The school was placed on probation in 2003.

Kleespies claimed that when the school lost the house system and heterogeneous classes were put into place, and when the school was subsequently placed on probation, many white students left. The deleveling of classes especially contributed to the white flight that took place. As Kimbrough put it, “That really pushed upper-middle class white families away from that school at that time.”

CRLS Today

While CRLS has changed significantly since the 70s, many community members still feel as though the inequity that existed fifty years ago exists today. Mr. Prince pointed out that there is less “outward” racial tension at CRLS than there was in the 70s, but that more subtle tensions and inequalities are still pervasive: “When you walk into a classroom, you can see it. You can see the difference. You can see one type of class has one type of kid and another type of class has another type of kid.” Mr. Prince also noted, “Parents will be like, ‘I want my kid out of that class ’cause these kids don’t know how to act.’” Mr. Prince commented that this reasoning is “code for” a class having students of color.

Ms. Banks added, “A couple of male teachers have told me that everyone expects them to do discipline in the hallways. So because they’re black males, they’re supposed to argue with these kids about staying in class, where previously, in my day, there was a level of respect that kids had for adults in general.”

Senior Marney O’Connor spent a year working on a graduation project about education at CRLS with a specific focus on students with Individualized Education Programs (IEPs). She observed that when students with IEPs are put together in a classroom—usually a CP classroom—the environment is not productive, which contributes to the stigma Mr. Prince referred to. “They’re all feeding off of each other’s frustration,” O’Connor said. She believes that this year’s Level Up initiative with English classes isn’t a complete change: “I feel like it’s just the same divide, only with a different title.”

Martin said it is “troubling” to her to hear about the achievement gap at CRLS, adding, “I didn’t see that when I was there.” She continued, noting, “Something’s happened over the years. There were a lot of us who went there, and many of us were—and are—very successful, whether you were black, white, or whatever.”

Kimbrough noted, “I really believe that diversity has always benefited white families more than black families in our city. I think there are kids from CRLS, white kids in particular, who are able to navigate our world and our country and its changing racial makeup in a much better way because they lived in Cambridge.”

Natalia Ruiz, a senior at CRLS, is a teaching assistant in a CP U.S. History 1 class. She said that she sees everyday how the kids are “very negatively affected by the achievement gap.” Given this, Ruiz said that “as a school we need to raise more awareness about [the achievement gap and] figure out why people are against reforms.”

Marileissy Ramirez Tejeda ‘18 said she felt as though the achievement gap hadn’t affected her until junior year. She was in a class with only one other “dark-skinned” person. The teacher told her that she “wouldn’t be able to put up with the workload of that class,” though Tejeda felt she was up to it.

Kimbrough commented, “If white families choose to stay in the district as we move forward with Level Up, I think that would be great.”

He continued, “If those families choose to leave … they are just leaving because the perceived education in that classroom will not be as good, because there are black and brown kids more with white kids in ways we haven’t seen in recent history at the high school.”

This piece also appears in our May print edition.

Correction: An earlier version of this piece mistakenly stated that Rindge Tech and Cambridge High and Latin merged in 1975. The schools merged to create Cambridge Rindge and Latin in 1977.