Diversity in Cambridge: Part 1

Cambridge Housing Policy’s Effect on Diversity

April 25, 2018

Cambridge is often heralded as a leader in diversity and inclusion. However, like virtually every American city, it has a tumultuous history when it comes to racism and discrimination. The first enslaved person arrived in Cambridge in 1638, and in the three and a half centuries since, Cambridge has not always lived up to its reputation of inclusivity. This is the first part in a Register Forum series tracing discriminatory policies in Cambridge over the years. Part one focuses on housing policy in the city and how it has impacted the city’s diversity.

Caught Between Progress & Reversion

Slavery existed in Cambridge until it was outlawed in Massachusetts in 1783. After this point, the city was still discriminatory—as was the rest of the country—but Cambridge became somewhat of a pioneer in creating a semblance of racial equality. This changed in the early 1900s, when the mainstreaming of racist ideologies happening around the country seeped into Cambridge.

In 1938, the city built two new public housing projects—Newtowne Court and Washington Elms in the Port neighborhood—offering subsidized housing to low-income families. At the time, the Cambridgeport area was the largest black community in Cambridge, but the new public housing apartments were given mostly to white families. Charles Sullivan, executive director of the Cambridge Historical Commission, told the Register Forum that the city of Cambridge “was not colorblind” in its distribution of these subsidized units.

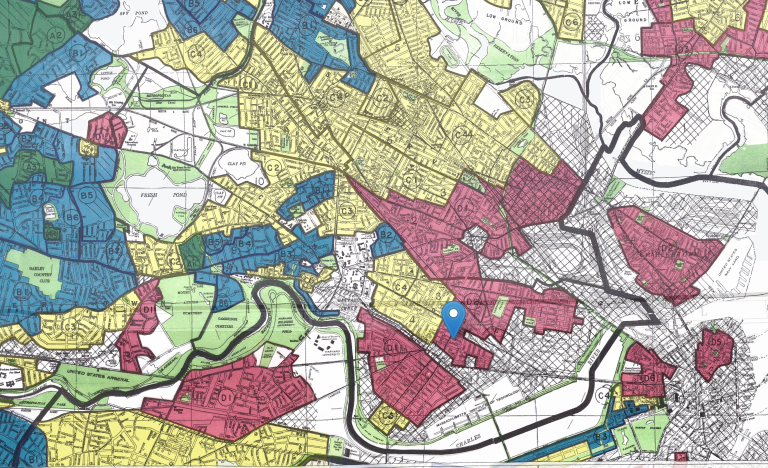

This racism was not isolated to just one neighborhood. Maps drawn in 1930 by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC)—which was created to help people buy houses as part of the New Deal—ranked neighborhoods in Cambridge based on their quality. Factors that determined this quality were traits such as “infiltration of Negro” and “Negro concentration.” Areas with a high number of African American families at the time, including Cambridgeport and what is now called mid-Cambridge, were almost always labeled as “definitely declining” or “hazardous.”

Pictured: HOLC’s redlined map of Cambridge in 1930.

These ratings determined which areas of Cambridge received loans from banks. Whiter neighborhoods such as areas in West Cambridge, deemed more desirable and profitable by the HOLC, were more likely to receive loans for new houses, effectively segregating the city.

Nevertheless, during World War II, many black Cantabrigians noted that they experienced a more hostile racial climate when they left the city to aid in the war effort. In Common Cause, Uncommon Courage by Sarah Boyer, Aiden Ward Sr., former pastor of the Abundant Life Church, recounted his experience going from Cambridge into the military: “I lived on 17 Andrew Street in Cambridge … I grew up in a neighborhood where there were black and white, so I had no fear of being among white boys. I felt comfortable with them.” Ward elaborated on meeting other soldiers, saying, “The fellows that I knew from Alabama and Mississippi weren’t like me. They were real southern men, and they didn’t really understand things. They still had a real hate in them. When we were in Petersburg, we saw that they still had the signs up—‘black and white.’ They knew all about that, where I didn’t.”

Other black Cantabrigians recall enjoying a prosperous life in the city during this time. Cantabrigian Dennis Dottin’s great-uncle, Conrad Dottin, moved to Cambridge from Barbados in 1904, and Dennis Dottin has lived here himself for 74 years. Dottin reminisced about his childhood in the mid 20th century: “We were the first family to have a TV. Kids used to come down to our house on Western Avenue and look in the window…I’ll never forget that. I think we may have been the first ones to have a telephone. We’re talking about 1949–1950—somewhere around there. I felt like I was rich. We were the rich family on the street—for blacks, anyhow.”

Along with these cheerful childhood memories, though, Dottin remembered encountering racism in Cambridge. He told the Register Forum, “There were certain parts in Cambridge where there was a conflict … Black people couldn’t even come down to East Cambridge—we were chased out of that area.”

Chandra Banks, who is a fifth- generation Cantabrigian and is now the Cambridge Public School District conflict mediator, grew up years after Dottin did but made a similar observation about East Cambridge, saying, “Black people didn’t go to East Cambridge. Never. My mother and this other woman went to a party up in East Cambridge, and the pastor—the father of the church—said, ‘Girls, girls, you know you don’t belong here. Go back to where you belong—let’s not have any funny business.’”

Urban Blight

Following WWII, there was a national housing crisis when many soldiers returned home after being deployed. In an attempt to expand housing opportunities for American families, the federal government passed the GI Bill. By investing in infrastructure like highways, the government opened up land for suburban development and offered to back mortgages for newly constructed homes. According to Gavin Kleespies, director of programs at the Massachusetts Historical Society, these policies “massively incentivized” moving to the suburbs for those who had the ability to do so. Those who had the ability to move to the suburbs, though, were almost exclusively white. Also known as “white flight,” this phenomenon gutted cities like Cambridge as their tax bases dropped. White flight also caused cities to turn into “urban blight,” which Kleespies told the Register Forum was “[a] code word for really heavy-handed development” that was displacing a lot of people, especially communities of color.

A component to this redevelopment plan in Cambridge was a proposal for a massive, six-lane highway, called the “Inner Belt,” intended to run through Cambridge into Roxbury. Construction of the highway was eventually blocked by widespread opposition, but it would have displaced 2,000 households and, notably, would not have run through predominantly white neighborhoods like Harvard Square.

Around this time, in the ’50s and ’60s, both Cambridge and Boston lost about 30% of their populations. Massachusetts had been a center of industry because of its proximity to waterways, but with the introduction of railroads and highways, these were no longer necessary for good business. Consequently, residents of the two cities moved to other cities where there were more jobs or suburbs were there were better living conditions.

Pictured: A childhood photo from Dennis Dottin.

Rising Rents

During this time, Harvard University and MIT University began to buy up large swaths of land in Cambridge as the institutions grew in international prominence. Graduate students started to flood the housing market, displacing families and increasing the divide between the schools and the rest of Cambridge. These graduate students, who often lived with roommates and were able to pay more, drove up rents in Cambridge.

Many Cantabrigians saw rent control as a way to protect Cambridge citizens. In order to contain the increasing rents and keep long-time Cambridge residents from being pushed out, the City of Cambridge instituted rent control in 1970. Rent control effectively froze rent, meaning tenants would pay the same rate on a unit in 1970 as they would in 1975, and so on.

Rent control applied to all buildings except for those with three or less units that were owner-occupied. However, given that there was no test to determine whether one could afford a market-rate home, many Cantabrigians who did not need a rent control rate were able to pay less than they otherwise would have.

In addition, rent control led to a substantial deterioration of housing stock in the city, as landlords had little incentive to invest in improvements to their properties, and there were few opportunities for renters to buy the houses they inhabited, as it was illegal to take a house off of rent control.

Mayor Marc McGovern, who comes from a long-time Cambridge family, said to the Register Forum, “There were downsides to rent control. There were a lot of people who were living in housing that was dilapidated because the landlords didn’t even get enough rent, practically, to pay property taxes—let alone keep their property up. Instead of the city stepping up and putting any money behind [affordable housing], they said, ‘We are going to balance this social value on the backs of private individuals.’”

The End of Rent Control

While many Cantabrigians saw rent control as a way to maintain Cambridge’s diversity, not everyone agreed that it was the best way to ensure this value. The most prominent opponent to rent control was the Small Property Owners Association (SPOA).

SPOA’s main argument was that property owners were unable to make a sufficient amount of money off of a rent-controlled property. SPOA also felt as though rent control was not doing what it was set out to do.

The association hired an economist from MIT to measure the demographics of tenants in rent-controlled apartments, who found that 90% of rent-controlled apartments were occupied by predominantly white, college-educated, single people.

President of the Harvard Square Business Association Denise Jillson ran SPOA for a decade, and she agreed that rent control hurt Cambridge’s diversity. According to Jillson, this is because it hurt small property owners—a diverse group themselves. When Jillson and her husband first moved to Cambridge, they lived in a rent-controlled apartment that her father-in-law owned. Her father-in-law had come to Cambridge from Portugal at the age of 42 with five kids. He didn’t speak English. He worked two and a half jobs to be able to buy his property on Berkshire Street, which Jillson and her husband eventually moved into.

Jillson got involved with SPOA after her experience with owning a rent-controlled property. In an interview with the Register Forum, she said that when she discovered the effects of rent control on property owners, she “developed an ulcer.” Jillson continued, “I am an eleventh-generation American. My family fought in the American Revolution. We fought for property rights. It’s always been about property—that’s the American Dream. So I buy this piece of property, and suddenly I realize that, guess what, it’s not really mine. The government is telling me how I can run it.”

Knowing that they could not get rid of rent control through a citywide decision, SPOA submitted a question to that year’s statewide ballot. In November of 1994, they narrowly won the campaign to abolish rent control, although the statewide measure actually lost in Cambridge itself.

Laurence Kimbrough, a member of the School Committee who has lived in Cambridge his whole life, said of the end of rent control, “In losing rent control, we certainly lost a good number of African American, middle-income families in the city.”

Dottin added that the rate increase following rent control was damaging to the black community: “How many black families were able to pay 3,400 [dollars] for a two/three bedroom? Plus, people [were] buying houses left and right for a million dollars or more—not too many black people have that kind of money.”

Many remember the end of rent control as leading to an exodus of middle-income black families, and this may well have been the case—but according to Cliff Cook, the city’s demographer, the total number of black families in Cambridge has stayed relatively stable since the end of rent control. According to census data, in 2000, people who identified as black or African American were 11.9% of the population, and in 2010 they were 11.7% of the population. Cook said, however, that until the next census in 2020, it is hard to come to any conclusions.

The Tech Boom

Following the change that the end of rent control brought to the Cambridge community, the dot com boom in the mid ’90s led to unprecedented expansion in Cambridge. Cambridge and Boston were uniquely positioned for this spike in commercial development given their proximity to a number of universities.

The increase in wealthy homeowners during the tech boom coincided with the end of rent control. Just as prices were allowed to increase dramatically for the first time since 1970, an influx of high-earning, young professionals flooded the housing market, leading to dramatic spikes in real estate costs.

Pictured: Denise Jillson, president of the Harvard Business Association.

Dottin spoke about the drastic change in rents during the late ’90s, saying, “I remember this one particular house on Western Avenue, they were paying $600 a month. Whoever bought the house, [when] they moved out, the first floor was $2,000. The rents just went totally out of whack…That was when rent control had ended. The rents went sky-high.”

Libby Gormley, a reporter for the podcast Backyard Cambridge who investigated rents in Cambridge, said in an interview with the Register Forum, “Cambridge is a huge hub for the biotech industry. And so because that industry attracts a lot of high paying jobs, the people who are taking those jobs can afford to pay the high cost of rent in Cambridge.”

She continued, saying, “It’s just concerning that what used to be a really neighborhood-oriented feel of the city is rapidly dissipating. It’s not a city where people can stay and raise kids and have this long history, because even people who have been here and have long family history—they’re getting pushed out.” Dottin agreed, saying, “Cambridge was like a village. Everybody knew everybody and they looked out for each other. That’s just not happening today.”

Recent Housing Policy

With new pressures leading to increasing housing prices in the city, Cambridge today is trying to find other ways to ensure that it maintains its socioeconomic and racial diversity by becoming a leader in affordable housing. Gormley noted that in comparison to a lot of other cities, Cambridge has one of the highest inclusionary zoning rates. Inclusionary zoning rates are regulations that require developers to make a certain percentage of the housing that they are building affordable. The inclusionary zoning rate in Cambridge was just raised to 20%, and Mayor McGovern believes that this rate finds the sweet spot between making sure enough affordable housing is being built and maintaining Cambridge’s desirability to developers. “When you are talking about a city-wide zoning [policy], 20% was the number [an outside consultant] felt you could reach without stifling development,” McGovern said.

Cambridge also uses linkage fees as a way to fund building for affordable housing. Linkage fees require developers to pay a certain dollar amount per square foot of new housing they develop. This money goes to an affordable housing trust fund run by the city government. Many argue that Cambridge could do more to ensure affordable housing for all residents who need it and thus more to ensure it remains a city that is diverse. Gormley says these arguments are usually just for extensions of these existing policies.

However, Gormley noted that there is only so much the city can do given the market’s behavior: “It’s sort of the natural forces of the market—people can afford to pay these high prices, so naturally the market is going to respond to that. And, too, it’s expensive to buy land here, and so it makes economic sense for developers to be charging these high prices—but that just squeezes out these lower-income people.”

Mayor McGovern believes there is more the city could be doing to make housing in Cambridge affordable. He would like to see changes to the zoning laws so that urban areas can become more dense, as would Jillson. Jillson commented, “If you think about Cambridge, you can’t go horizontal. The only way you’re gonna go is vertical … We just have no more space.”

Dottin expressed his feelings about Cambridge’s current situation, saying, “I’m just hoping a lot of the people who grew up here don’t have to move out.” Dottin worries that the businesses and institutions coming into Cambridge fail to serve the residents adequately. If anything, he believes they force those residents to move out.

He hopes that his grandchildren, who now make up the fifth generation of the Dottin family in Cambridge, will be able to experience a Cambridge similar to the one he grew up in: “I’m just hoping the kids who grew up here can stay here, get a good job, and raise our families—just like we did.”

Look for the second article in this Register Forum series in next month’s edition. Part two will focus on the role race has played in Cambridge’s schools. This piece also appears in our March/April print edition. Correction: An earlier version of this piece mistakenly stated that Newtowne Court and Washington Elms were in the Cambridgeport neighborhood.