A National Issue Hits Home: The Opioid Epidemic and Its Impact on Cambridge

March 23, 2020

A man is sitting on a public bus in Upper Darby, Pennsylvania. The grainy security camera footage shows him sitting straight up and looking at the roof of the bus. He begins to sway, and then, suddenly, he collapses into the center aisle of the bus. The man lies shaking in the aisle and the video cuts to a scene of five police officers standing over him. One of the officers sprays a dose of Narcan, an overdose-reversing drug known by its generic name as naloxone, into the man’s nose, and he stirs as they carry him off the bus.

Scenes like this are not uncommon in America, a nation that had 70,000 deaths from drug overdoses in 2017, 48,000 of them from opioids. 131 Americans fatally overdosed from opioids every single day in 2017. In fact, more Americans fatally overdosed in that year than were killed in the wars in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan combined.

The opioid crisis that has emerged over the past three decades has had a devastating impact across the United States. Certain regions have been hit harder than others, but the crisis has affected every community in the nation, Cambridge included. While numbers play a large role in capturing the scope of the crisis, statistics can mask the stories of real people whose lives have been permanently impacted. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), over 400,000 Americans have died from opioid-related overdoses since 1999. However, that number doesn’t count the hundreds of thousands who have lost friends or family members, or those who have died from maladies related to their addictions.

To get a sense of how the opioid crisis started, one first must understand what opioids are. Opioids are a class of narcotics derived from the opium poppy plant. They make users relax and can relieve pain and are therefore prescribed by doctors as painkillers. They are also highly addictive, causing habits that are immensely hard to change. Opioids can be naturally derived like heroin or opium, or be made in a laboratory like oxycodone or morphine. Although prescription opioids are generally considered the root cause of the epidemic, drugs like heroin and the deadly synthetic opioid fentanyl are the main drivers of fatal overdoses, as they are unregulated and much more potent.

The history of the opioid epidemic in the United States is rooted in the 1980s and 1990s when chronic pain began to be recognized and treated as a major health problem. Before that, opioids were only prescribed for short-term pain or terminal conditions like cancer. Seeing a lucrative market, in the mid-90s pharmaceutical companies began to introduce new opioid-based products, like the highly popular Oxycontin from Purdue Pharma. These same companies started major campaigns emphasizing the safety of these new drugs and the low likelihood of their patients becoming addicted, wildly inaccurate claims based on shoddy science and deeply flawed studies. Doctors aggressively prescribed opioids to chronic pain patients under the mistaken belief that their patients would not become addicted, and pharmaceutical companies made many billions of dollars. The first phase of the epidemic began with easily available prescriptions that allowed users to stockpile drugs and sell them on the black market, further flooding the nation with opioids. Hundreds of thousands of new addicts were created. By 1999, the CDC reported 16,849 fatal overdoses, compared to 8,400 in 1990.

As the scope of the epidemic became clear in the late 2000s, the federal government responded, tightening restrictions on the quantities of drugs doctors could prescribe and encouraging pharmaceutical companies to alter their formulas to make their products harder to misuse. By this point, there was an entire generation of opioid addicts who switched over to the cheaper and more easily available heroin, which could be bought for $5, as opposed to a $50 prescription Percocet pill. Around 2013, the third phase of the epidemic came when dealers began to lace their supplies with fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is 50 to 100 times more potent than heroin. Kieth Humphreys, a Stanford psychiatrist and former White House drug policy advisor, said of these three phases: “Basically, we have three epidemics on top of each other. There are plenty of people using all three drugs. And there are plenty of people who start on one and die on another.”

While prescription guidelines are much stricter now, deaths are still skyrocketing. 2017, the most recent year that data on overdoses is available for, was the deadliest year in American history for overdoses.

The opioid crisis has spread to every community in the nation. While the states with the highest rates of opioid overdoses—West Virginia, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Kentucky—may be unsurprising given where the news coverage around the epidemic focuses, Massachusetts has the ninth-highest fatal overdose rate in the nation. The state saw 2,056 fatal opioid-related overdoses in 2017, compared to just 379 in 2000. A report from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health shows that fatal overdoses are down 6% in 2019 compared to last year, bucking a nationwide trend of increase. Despite this positive news, fentanyl was present in 93% of deaths in 2019, as opposed to 89% in 2018. Even more disturbing, according to new data never before compiled by the state, 2% of mothers and new babies had been exposed to opioids. Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker said that the report “affirms that our multi-pronged approach to the opioid epidemic is making a difference. Although we’ve made progress, we must continue to focus our law enforcement efforts on getting fentanyl off of our streets and out of our neighborhoods.”

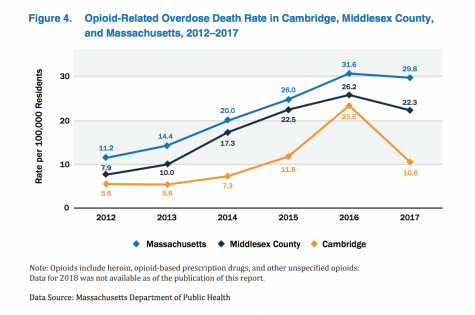

Just as Massachusetts has been hit hard by the opioid crisis, Cambridge has been as well. According to the Cambridge City Manager’s Opioid Working Group, fatal opioid-related overdoses in Cambridge peaked in 2016, with 41 deaths. 2017 saw a major drop, with only 21 deaths citywide. The statewide opioid-related overdose rate per 100,000 population was 29.8 in 2017, and the rate for Middlesex County was 22.3. Cambridge had a rate of just 10.6, down from 23.5 in 2016.

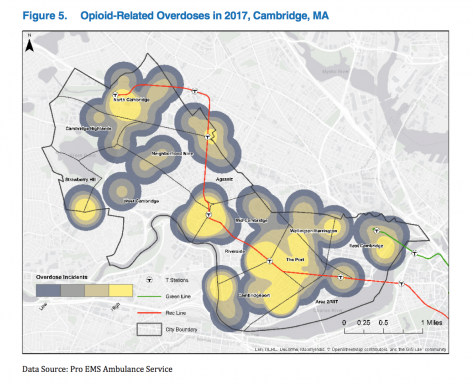

The Cambridge Public Health Department (CPHD)’s Opioid Data Report, released in 2018 to provide the public with information on the epidemic’s impact in Cambridge, shed some light on the characteristics of the local epidemic. Heroin was the main driver of overdoses in the city for every year data is available, although the CPHD reported that “since 2014, the rate of heroin or likely heroin present in people who died from an opioid-related overdose has been decreasing, while the presence of fentanyl and cocaine is still trending upward.” According to the report, overdose incidents occurred in every neighborhood of Cambridge in 2017 but were concentrated in Central Square, Harvard Square, Alewife and Porter Square on the Red Line, and near Lechmere on the Green Line.

On the frontlines of this epidemic are first responders and medical professionals who have important insight into its characteristics and impacts. Dr. Caleb Dresser, an ER doctor at Boston’s Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, has treated countless patients suffering from the effects of opioid addiction and was interviewed by the Register Forum. Dresser has seen many patients who are actively experiencing opioid overdoses, but he also raised an oft-ignored aspect of the epidemic: “the consequences of opioid use and addiction [aside from death], which are numerous and can be very severe.” Dr. Dresser described people “who’ve had bacteria infect their lungs or their spine, undergone multiple surgeries, or are hospitalized for weeks or months, mostly dealing with the effects of getting bad bacteria in their bloodstream.”

Dr. Dresser also stated that the statistics on fatal overdoses do not provide the whole story. “In terms of angles I have heard less of in the media, [one] is what are the long-term life consequences beyond did you overdose and die or not,” he said. Dr. Dresser believes that this aspect of the epidemic deserves more attention. “For every person that overdoses and dies, there are many that overdose or use for some amount of time and don’t. They carry a psychological toll and, in many cases, a medical and physical toll on their bodies: severe infections, surgeries, chronic health problems,” he explained. “Even when people get clean, the stigma associated with a lot of this can interfere with some of their professional prospects.” These harder-to-quantify impacts are not limited to a single sector of the population. A Sheriff’s Deputy in Montgomery County, Ohio, Walter Bender, stressed in a TIME magazine special report that opioids “reach every part of society: blue-collar, white-collar, everybody.”

Dr. Dresser echoed Deputy Bender. “While most communities have a subset of people that are regular users of opioids, you will get people that might surprise you showing up at the emergency room with overdoses.” Dr. Dresser continued, “This is affecting every income bracket, in different ways—every possible description of how you could get into opioids, I have heard.”

In the face of this wide-ranging crisis, the City Manager’s Opioid Working Group made a series of recommendations in 2018 to remedy the crisis. A major recommendation was to continue the city’s efforts to increase access to naloxone, the drug that temporarily reverses the effects of an opioid overdose long enough for emergency services to get the patient to a hospital. According to the Cambridge Chronicle, every Cambridge Police officer now carries Narcan while on duty (firefighters and ambulance personnel were already equipped with the drug). The Working Group also recommended that city buildings be equipped with medical kits containing Narcan. City officials followed through, placing kits containing naloxone in 28 buildings across the city. According to the Opioid Data Report, in 2017 naloxone was administered 218 times in the city, 56% by bystanders rather than first responders. Dr. Dresser said, “Essentially every overdose that I see in the ER has received naloxone before the victim reaches the hospital,” and described the increased availability of naloxone as “a big part of reducing fatal overdoses in the field.”

Another major recommendation in the report was for the CPHD to continue improving education and increasing awareness about the epidemic. The Department’s Overdose Prevention and Education Network (OPEN) works to promote information about opioid treatment by reaching out to pharmacists in Cambridge to advocate for pharmacy-based naloxone distribution. They also help educate the public about the state’s Good Samaritan Law, which protects anyone who calls 911 about a drug overdose from being arrested. Dr. Dresser stated that ER doctors now prescribe naloxone to all patients who come into the hospital with an opioid-related issue and that “most pharmacies now have standing orders to provide naloxone on an as-requested basis.”

With the Opioid Working Group’s support, the Cambridge Health Alliance (CHA) has also undertaken a variety of major efforts in response to the epidemic. They have increased education for medical providers on prescribing opioids and have pursued non-pharmaceutical methods of treating chronic pain, such as physical therapy and healthy lifestyle choices. CHA has created plans to taper patients off opioids and established “a multidisciplinary consultation service for providers to get advice on challenging pain/addiction cases.” CHA also provides access to a variety of treatment programs for opioid users around metro Boston.

All of these well-funded and highly-supported efforts have arguably had a real impact on the epidemic in Cambridge. In the first report from the Opioid Working Group, co-chairs Assad Shayeh M.D. and Cambridge Police Commissioner Branville Bard wrote, “City officials, community partners, nonprofit and social service organizations, and residents have come together in partnership to develop an integrated and robust response across the continuum of prevention, intervention, treatment, and recovery.” Dr. Shayeh and Bard continued: “This collective work has seen results—the overdose death rate in Cambridge decreased from 2016 to 2017, the first decline in 7 years, and this downward trend continued through 2018.” Although data from 2018 and 2019 is not yet available, it is very possible that the city may have experienced another decline in fatal overdoses, potentially corresponding to the statewide decline that took place in 2019.

Despite these promising numbers in Massachusetts and Cambridge, this crisis is far from over. Although fatal overdoses may be decreasing in the Cambridge community, this is not the case nationwide. As previously mentioned, for the last year when data is available (2017), overdose deaths were by far the highest in American history. Although the city and the state’s efforts seem to be having an effect, there are still a great many Cantabridgians struggling with opioid addiction. Dr. Dresser emphasized, “Help is available, and there are a lot of good organizations that are doing a lot of good work around this. Recovery is very much possible.”